|

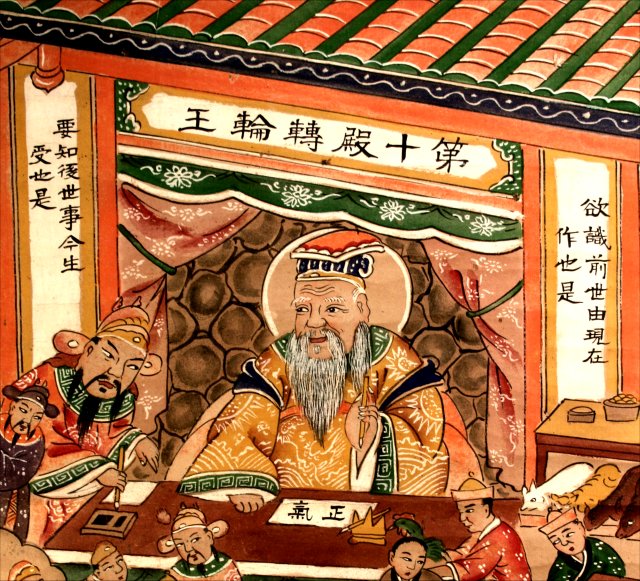

Tenth court - The Wheel-turning King |

| Large image |

| Previous court |

| Main Gates |

| Compare to a scroll acquired from Shanghai |

| Comments |

| First court |

| Second court |

| Third court |

| Fourth court |

| Fifth court |

| Sixth court |

| Seventh court |

| Eighth court |

| Ninth court |

| Tenth court |

The medium: Hell on an assembly line

The power of hell paintings to bring about moral transformation had a well-established history, and in an account from the Record of famous painters of the Tang dynasty, an elderly monk at the Bright Cloud Temple of Chang’an recalled how the famous painter Wu Daozi 吳道子 (680-c.760) intensely affected his viewers:

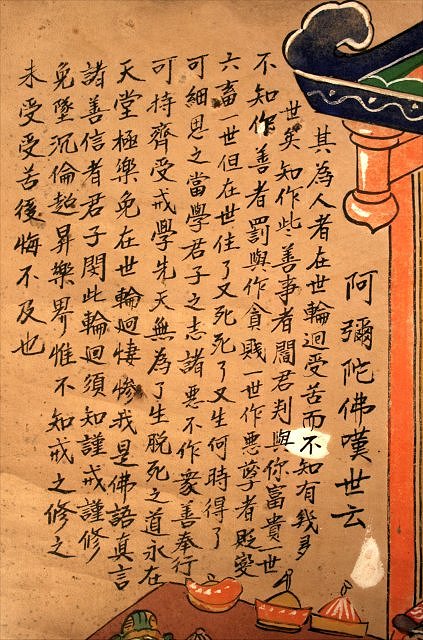

吳生畫此寺地獄變相時,京都屠沽漁罟之輩,見之而懼罪改業者,往往有之,率皆修善。

When Master Wu painted instructional pictures about hell in this temple, most of those people living in the capital who had been butchers and wine sellers, fishermen and small game hunters took fright because of their sins and changed their professions once they saw his painting, straightaway cultivating goodness.

While Wu Daozi’s abilities may be exaggerated here, provocative hell images became a regular subject of wall paintings, scripture handscrolls, cliff grottos and indeed hanging scrolls during the Tang and Song dynasties.

Yet no famous personage like Wu Daozi painted any of the hell scrolls from the 18th-21st centuries in this collection; no identifiable artist painted them at all. As ritual implements, most of them were not the masterpieces of artists working in their studios but instead the products of artisans employed in workshops. When they became tattered after much use, they were thrown away and replaced.

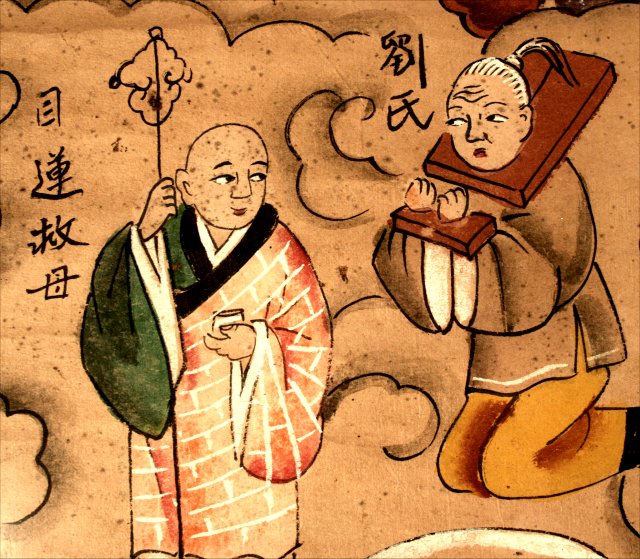

Evidence of their workshop origins is in their mass production. For example, the A-series was originally acquired in Taiwan in the early 1970s, but I obtained a doppelganger for this tenth scroll in Shanghai forty years later. A side-by-side comparison demonstrates how these two paintings are not individual works of art and have only minor differences in color or detail such as in a man's robe, a roof tile or a background window. For a second example, S23 is almost identical to one in Neal Donnelly’s published collection, A journey through Chinese hell (p. 59).

Lothar Ledderose describes the modular production of early hell-scroll production as follows:

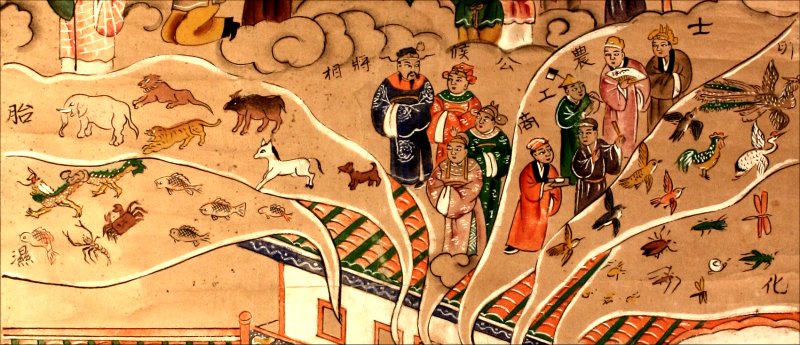

It is obvious that single figures and groups, as well as other motifs, were transferred onto the picture ground by the mechanical means of stencils. Most likely, the painters had a pounce – a sheet of paper on which the contour lines of a motif are indicated by small holes. When these sheets were laid on the painting surface, and they were pounced with black or colored powder, the contours became visible beneath.... Once the dotted outlines were complete, a master painter reworked them in ink using a brush. In a third stage, other artisans assumed the detailed execution and filled in the colors. Such a division of labor has a long tradition in Buddhist painting.

Thus some artisans may have specialized in drawing (or tracing out) the magistrates, others writing the characters and still others adding the color as if the scrolls went down a kind of assembly line.

The workshop was probably only one means of reproduction, one that resulted in the most similar forms, arrangements of those forms, size, texts, execution styles and coloring. A second kind of reproduction was presumably a reliance upon painting manuals akin to the Ancestral treasures of painting or the famous Mustard seed garden manual of painting. These small, monochrome block-printed books would have standardized the forms, arrangements of those forms and texts but not necessarily the size, style and coloring. In this collection, good examples of different scrolls probably informed by the same painting manual are A04 relative to S18 and I08 relative to S04, among others. In much more recent times, I personally commissioned the N-series in 2013, and we located the painting manual that had informed it, namely the Sanjiao shengxiang huaji 三教聖像畵集 or Collected drawings of iconic images in the Three Teachings (the teachings being Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism). For an example of how close the monochrome drawing and resultant painting can now be, see N01 relative to its guidebook image. Using these painting manuals, artisans need not have replicated the whole of a hell scroll’s layout, and at times they mixed and matched halves, thirds or even just individual torture scenes as needed. There is much evidence of that flexibility in this study collection as well.

It’s possible that some of these hell scrolls were not the product of workshops and manuals, and a few of them (to my untrained eye) would seem to exhibit more flowing, expressive, painterly qualities such as the M-series, S10 and S17. More importantly, identifying their general artisan origins is by no means to denigrate the scrolls. Colorful and heavy with allusions, they still evoked emotion from horror to humor, and they reached out to a much greater audience than would have ever seen a particular artist’s masterpiece. Yet instead of merely entertaining their viewers, they first and foremost warned of an agonizing reality to come that was anything but entertaining.

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||