|

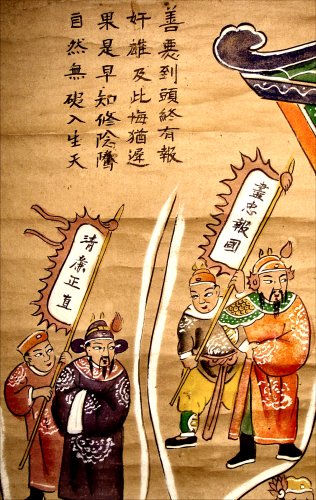

Sixth court - King Bian Cheng |

| Large image |

| Previous court |

| Next court |

| Main Gates |

| Compare to an additional single scroll |

| Comments |

| First court |

| Second court |

| Third court |

| Fourth court |

| Fifth court |

| Sixth court |

| Seventh court |

| Eighth court |

| Ninth court |

| Tenth court |

The living intercede on behalf of the dead

Each of the ten hell magistrates was associated with a particular day of the year on which the living could repent and swear an oath to live moral lives, the goal being that they themselves might avoid torture in hell. In terms of their loved ones being tortured, the living in some traditions offered ten sacrifices after a person's death, sacrifices that were each seven days apart. Other traditions stipulated seven sacrifices spaced seven days apart followed by an eighth sacrifice at the hundredth-day anniversary, a ninth at the first-year anniversary and a final sacrifice at the third-year anniversary. (In that way, the latter sacrificial schedule appears to gesture toward the Confucian three-year mourning period.)

In a scene common to other sets of scrolls, here the living act on behalf of the dead to mitigate their tortures or even to exonerate them entirely. The rotating cylinder above and to the left of the pond is for a ritual known as qianzang 牽藏 (alt. qian chezang 牽車藏) performed by filial descendants to draw their ancestors up from hell through this chambered device to be reborn in heaven. While priests read sutras and children burned incense, the paper figurines on the side represented the dead as they moved up level by level during the ceremony. (This ritual continues to be performed today, often with specific reference to freeing the dead from the blood pond.)

Visually notetworthy is how only the Buddhist monk is literally able to reach over the gap dividing the living from the dead, thereby enabling the dead to leave their plight. In other sets of hell scrolls, the banner draping into pool is an edict that ends the torture, reading, "Pass through death toward rebirth." Especially after leaving their summer retreats during which they straddled the secular and sacred worlds, Buddhist monks in the middle of the seventh lunar month were particularly efficacious in channeling the sacrifices of descendents to their ancestors. (In various sutras and Buddhist narratives, direct sacrifices between offspring and ancestors were relatively ineffective without Buddhist specialists serving as intermediaries.) Hence part of Buddhism's historical success was due to its ability to piggyback on the existing ancestral cult.