|

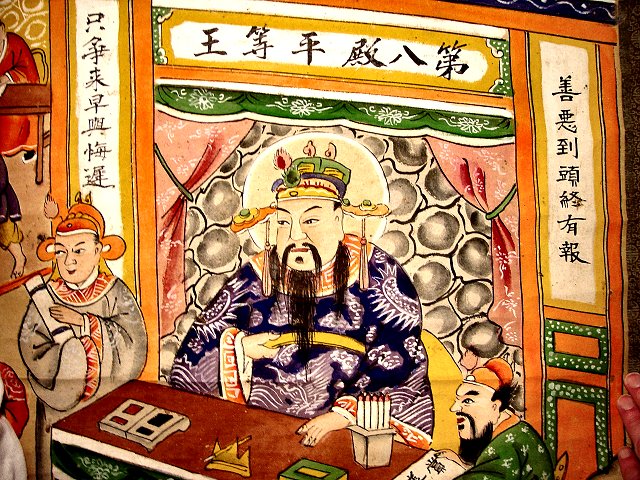

Eighth court - King Ping Deng |

| Large image |

| Previous court |

| Next court |

| Main Gates |

| Comments |

| First court |

| Second court |

| Third court |

| Fourth court |

| Fifth court |

| Sixth court |

| Seventh court |

| Eighth court |

| Ninth court |

| Tenth court |

Native and foreign magistrates ruling hell

Pictorial and textual surveys of hell in late imperial China are an amalgamation of doctrine (e.g. sutras), practice (e.g. the Ghost festival), narrative literature (e.g. about Taizong, Yue Fei, Guanyin or Mulian) and contemporary patterns of daily life (e.g. bureaucracy and economics). Operatic costumes are donned by a cast performing ghost stories that occasionally allude to philosophical ideas such as sunyata and no-self. These places of survey are a kind of meeting ground in the public memory for all the diverse perspectives about hell.

The ten magistrates or kings themselves evince this diversity of background. At least one probably predates Buddhism, namely King Taishan of the seventh hell who oversaw the realm of the dead two millennia ago in the Han dynasty. Taishan, or “Mt. Tai,” is often conflated with the Dongyue 東嶽, or “Eastern Peak” (e.g. S25) and prior to the ten magistrates, he oversaw the life and death of humans along with the Superintendent of Lifespans 司命 and the Superintendent of Records 司錄. Dongyue has been called “the Chinese equivalent of King Yama,” and he along with his aids continue to coexist as a set of gods with their own temples, rituals and scrolls.

The origins of some of the ten magistrates as they evolved in middle imperial China is a mystery, but at least two – Yama and Cakravartiraja – are immigrants from India and eventually came to oversee the fifth and tenth hells respectively. Relevant to the eighth hell, King Pingdeng may also have foreign origins.

Manichaeism spread out from Persia to Rome in the 4th century C.E., and there is evidence for its presence in Tang dynasty China as early as 732 C.E. This religion adopted and adapted major elements of the other religions that geographically surrounded it, resulting in Jesus and the Buddha working side-by-side for the salvation of humankind. In Manichaean documents excavated at Dunhuang, the devout might choose to petition Yama because he was "really the compassionate thinking of Jesus." King Pingdeng directly figures into various Manichaean hymns as in the following extract from a piece pondering how a person's death exemplified impermanence, here translated by Tsui Chi:

Only the shameful deeds and the evil doings

Will become burdens on his back after that day of impermanence:

Before the King of the Balance [i.e. King Pengdeng] all his reasons are unjustifiable,

And he goes through transmigration for birth-and-death tortures,

Once again to be bound and controlled by the king of devils,

And grow gradually in impurity if no good chance is met:

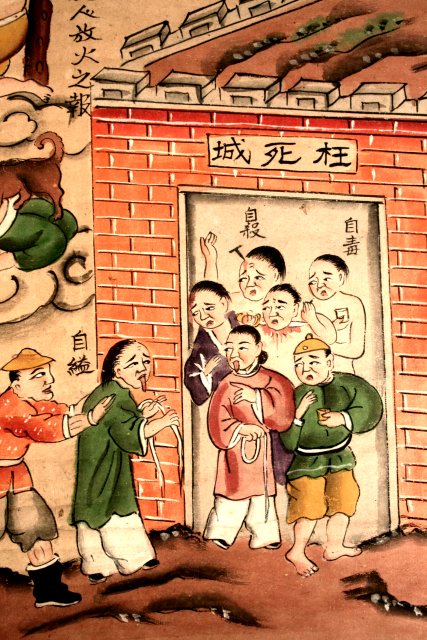

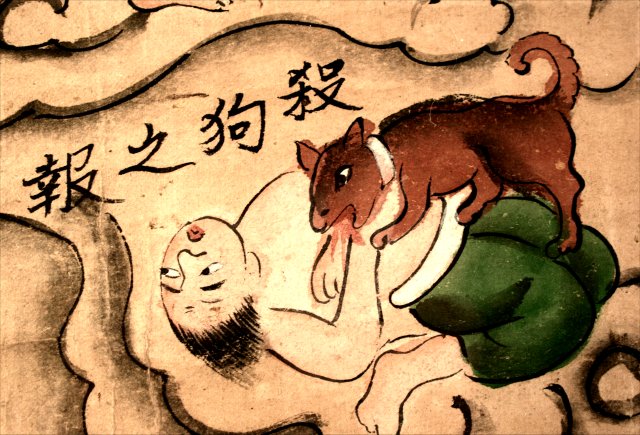

He will enter the earth-dungeon (i.e. hell) or will be burnt out,

Or will be imprisoned with the devils, in eternal prison.

Songs and pleasure, dancing and laughter, and all music,

Eating and gorging a hundred delicacies, and management of lands and houses

Are like visions in a dream which disappear when he wakes -

Think carefully, and nothing seems reliable.

The temporal relations of a family, which are a mundane truth,

How far do they differ from that of staying at a travellers' inn?

Masses of persons stop and rest together for a night;

In the morning, they separate and return to their own lands?

Wife and concubine, sons and daughters are like creditors,

All existing because of mutual injuries in the past;

They are all enemies and robbers with affections,

And one is therefore bound to repay them their strength.

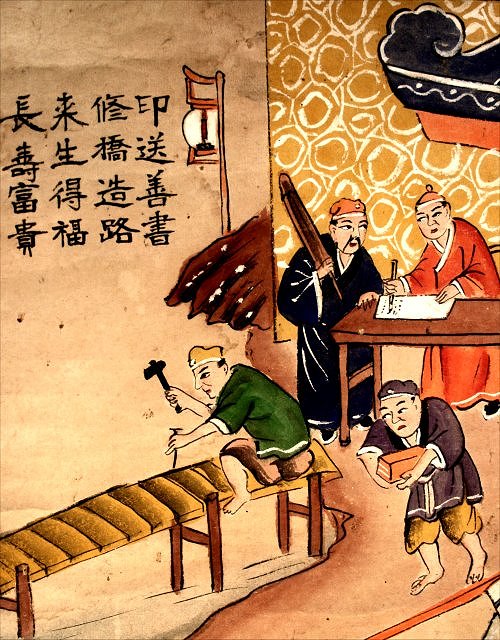

Elsewhere in the Manichaean texts, the good who come before King Pingdeng are led off to a place "where in the land roads are flat and even, and the sound of Sanskrit chantings spreads round, continuing and hovering." That description closely echoes the Western Paradise or "Pure Land" of Amitabha Buddha, and some versions of King Pingdeng's hell indeed show a bridge leading off to the Western Paradise (although this may be coincidental).

There remains one more peculiarity about King Pingdeng of the eighth hell: he often swaps places with King Dushi of the ninth hell. In hell scrolls, Jade records and narratives about purgatorial visits, the two are interchangeable, although Pingdeng tends to keep to the eighth. (In twenty-seven pictorial and textual surveys at my disposal, Pingdeng rules the eighth and Dushi the ninth in two-thirds of them.)