|

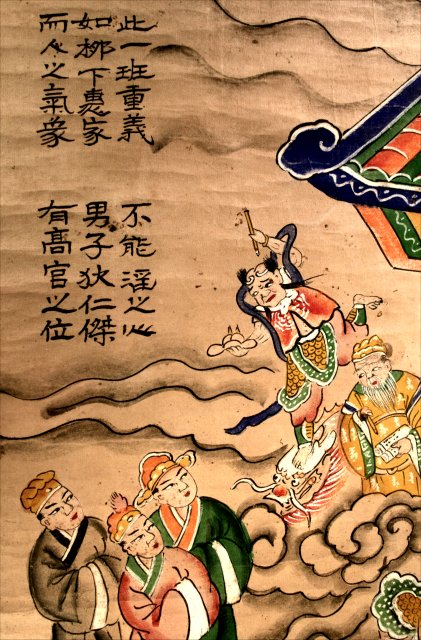

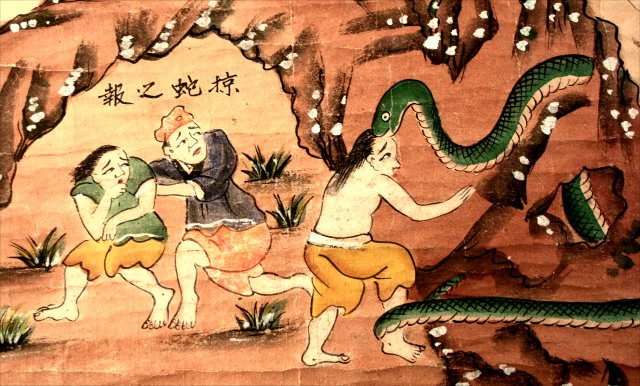

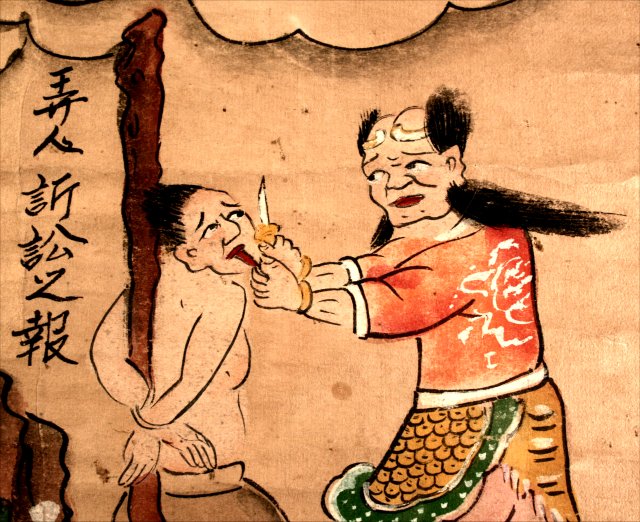

Ninth court - King Du Shi |

| Large image |

| Previous court |

| Next court |

| Main Gates |

| Comments |

| First court |

| Second court |

| Third court |

| Fourth court |

| Fifth court |

| Sixth court |

| Seventh court |

| Eighth court |

| Ninth court |

| Tenth court |

The multi-media spectacle of hell

Most likely compiled sometime between 720 and 908 C.E., The scripture of the ten kings was a sung, chanted and worshipped text that survives in several recensions. The illustrated versions of this Tang work are among the ancestors to these scrolls, and they already spelled out the need to behave properly. By the time the dead had reached the ninth hell, the living were observing the anniversary of their new ancestor’s death – see the schedule described at the sixth hell – and Stephen Teiser translates the scripture’s song coinciding with King Dushi's hell as follows:

At one year they pass here, turning about in suffering and grief, depending on what merit their sons and daughters have cultivated.

The wheel of rebirth in the six paths is revolving, still not settled;

Commission a scripture or commission an image, and they will emerge from the stream of delusion.

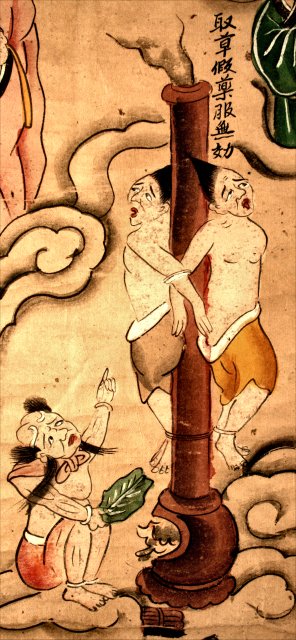

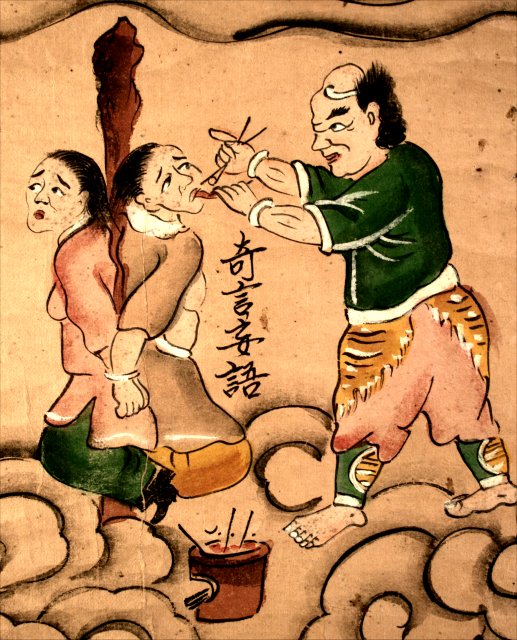

When the living commissioned a scripture or image, it generated a fixed amount of merit that could then be transferred to the dead, mitigating their tortures and improving their rebirth.

Fast forwarding to the era of the hell scrolls on this website (18th-21st centuries) when print culture made the propagation of texts easier, these scrolls still allude to the merit generated from financing the publication of “books on goodness” (shanshu 善書) as illustrated in the upper left corner of the previous scroll. The Jade registers are one example of such books, as are the various Ledgers of merit and demerit which literally grade and assign numerical values to moral and immoral acts. Using the latter, the faithful could tally their own merit scores every day in the same way that the supernatural agencies who had them under surveillance were doing. (For an example of a hell court weighing someone’s resultant ledgers on a steelyard, see L10.)

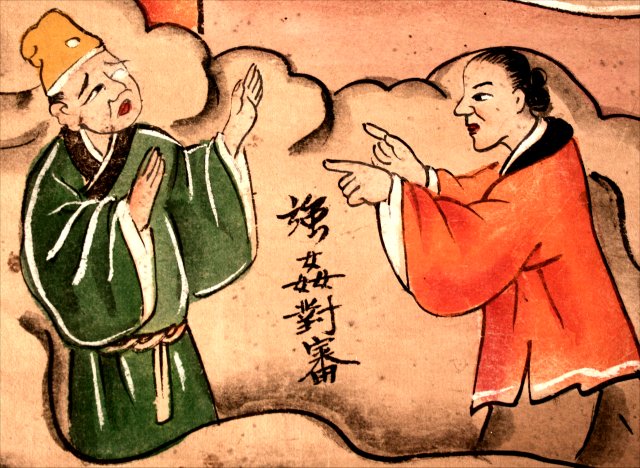

Thus the hell scrolls must be viewed within a constellation of morality-advocating media in late imperial China. Other such media ranged from the popular opera of Mulian rescuing his mother in hell, to ethical instructions inscribed on temple walls left behind by one’s ancestors. Guo Qitao identifies still other ways how the people were being advised to do good:

These moral exhortations [promoting the popular Confucian norm] were not just written down in lineage rules but were frequently read aloud to kinspeople (and more subtly conveyed through ritual and dramatic performances). The reading assembly known as the village lecture (xiangyue 鄉約) was popular in the mid-Ming and through early Qing.... Twice every month, kinspeople assembled in the ancestral halls to listen to the reading of the Sacred edicts and lineage rules. After the readings, participants discussed the good behavior and misdeeds of the kinsfolk, which were then recorded separately in a shanbu 善簿 (the book recording virtues) and an ebu 惡簿 (the book recording misdeeds) for reward or punishment. The shanbu and ebu format was most likely a metamorphosed form or an extension of Hongwu’s Pavilion for Declaring Goodness and Pavilion for Extending Clarity (shenming ting, which published the names and wrongdoings of criminals as warnings to others).

Hence while hell’s own warnings were depicted in pictures and texts, in opera performances and annual festivals, the hell scroll genre as a whole also coexisted with other moral-exhorting media, ranging from ledgers to lectures, as people learned how to quantify their merit and behave.

Yet could merit ever be fully quantified so that the living might comfortably approach death without fear of torture? King Dushi’s couplets would here suggest otherwise: “All the myriad things can't be analyzed through human calculations, and one's whole life is dictated by fate.”