|

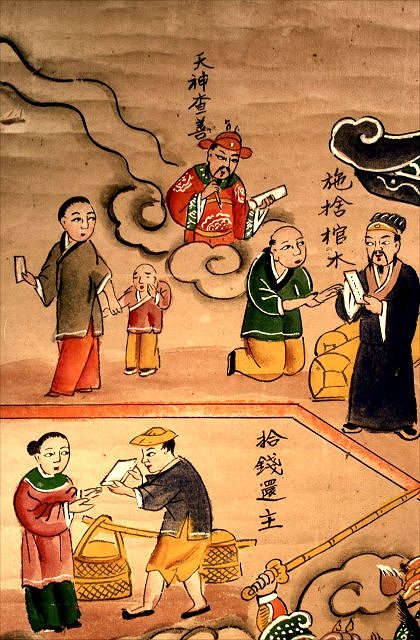

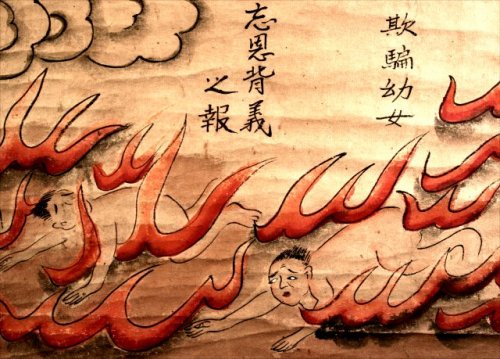

Seventh court - The King of Tai Mountain |

| Large image |

| Previous court |

| Next court |

| Main Gates |

| Comments |

| First court |

| Second court |

| Third court |

| Fourth court |

| Fifth court |

| Sixth court |

| Seventh court |

| Eighth court |

| Ninth court |

| Tenth court |

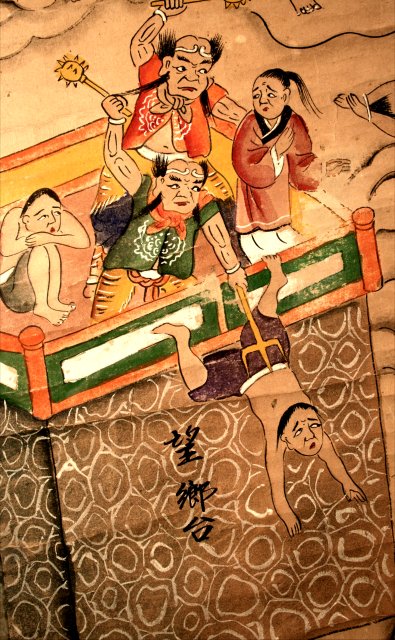

On one hand, descendants might anxiously endeavor to help out the dead with their offerings, music and incense as seen in the sixth hell; on the other hand, they might not care at all, as seen here in the seventh. This depressing realization becomes visually manifested in the common motif of the "Terrace for viewing one's home village" where the dead look back to learn that the living can't and often won't help them through their times of torture. According to some versions of the Jade registers, no good people ever ascend this terrace, and once on its top, the bad look back at the living to see how their last wishes were disregarded, their spouses remarried and their hoarded wealth wantonly wasted by thoughtless children.

This landmark still towers in hell today. The Temple of the Sages in Tai Chu, Taiwan, has published a series of spirit journeys to hell that took place between 1976 and 1978, and in his field trip, a monk by the name of Yang Ts'ien interviewed various hell kings, officials and tortured souls whom he met along the way. At one point, he asked King Yama why one particular old man was crying while standing atop this terrace, and Yama replied:

This old man had sinned heavily in his life. He later endured torment in hell which is now drawing to an end. He comes to the Platform for Vision of Native Place [a.k.a. the Terrace for viewing one's home village] to look back at his children and grandchildren. Now, he realizes that his offspring have no feelings whatsoever for him. He finds that some are absorbed in watching television, the others are relaxing idly in their rooms. None of them has any recollection of his onetime existence. He recalls the pain and labour he experienced in his lifetime for the sake of his progeny, and now their indifference dumbfounds him exceedingly.

The "Terrace for viewing one's home village" thus constitutes one of the psychological tortures among the many physical ones in hell.

Yet here we must make a distinction between symbol and explanatory context, the former being simpler and more stable than the latter. The exceedingly popular Mulian opera is about a filial monk endeavoring to rescue his mother in hell, and when his mother was escorted by this terrace, she learned its purpose:

何為望鄉臺?此臺天造地設,凡人一朝死後,骨肉未免挂念,所以登臺一望便見家鄉。

What is the “Terrace for viewing one’s home village”? Heaven established and earth erected this terrace because soon after people die and while their flesh-and-blood kindred are still thinking about them, the dead can climb up this terrace to gaze far and wide and are thereby able to see their home and village.

Yet she herself was not allowed to climb the terrace because only good people were allowed up there. People with black hearts instead had their vision blocked by black clouds. In other words, the "Terrace for viewing one's home village" may be static, but its explanation and purpose may differ even to the point of making this landmark either a positive or negative experience.

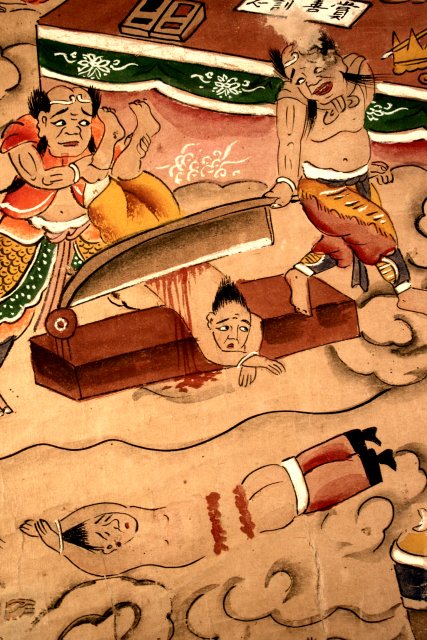

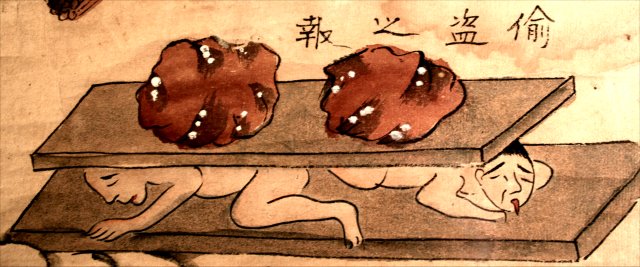

Other fixed images in hell also evince unfixed contexts. For example, hell scrolls usually show demons hoisting the damned onto a single sword tree (e.g. here in the fifth court), but in the earliest texts from India, there was a whole forest of sword trees, and the damned were forced to walk through that forest during a horrendous wind storm. In later Chinese texts, the damned were forced to climb the tree or, in a deluded state, they willingly climbed them out of lust for the beautiful woman they had seen in the topmost branches. (Of course, once they got to the top, they then saw her beckoning to them from the ground, and down they went. And up they went. And down they went.) For a second example, the superheated copper pillar or flue is equally popular in these scrolls (e.g. here in the ninth court), used to torture quack doctors, swindlers and adulterers alike. Some texts tell us the damned were physically bound to the pillar. Others say they were forced to climb that pillar to evade being beaten. Still others tell us the dead, again in a deluded state, willingly embraced the pillar as if it were their adulterous lover until they were burned up in passionate lovemaking. Just as the tortures were not particular to certain hells or earmarked for certain sins (as discussed at the fourth hell), their explanations and usages were often inconsistent as well. Hence the landmarks and tortures of hell must be viewed with a bifocal lens that distinguishes between stable, simple symbols and their more variable, complex contexts.