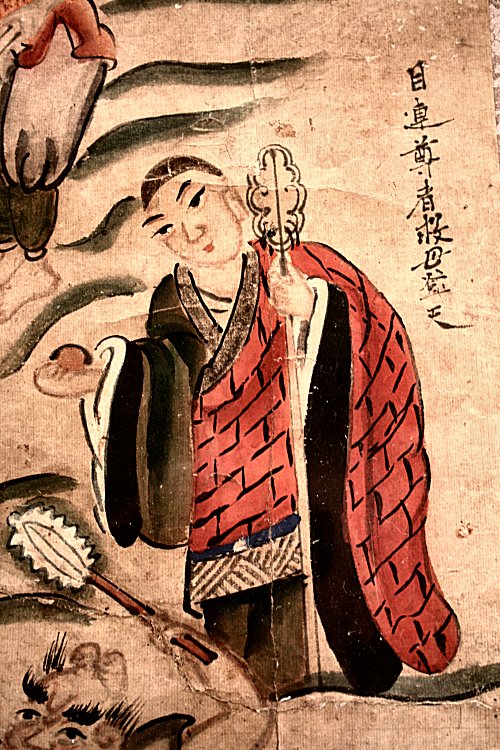

1. "Mulian rescues his mother and ascends to the heavenly halls"

Because it was a widely produced popular opera, Mulian's rescue of his mother in hell was perhaps the greatest influence on the notion of hell in late imperial China, and depictions of Mulian appear in at least nine (probably eleven) scrolls in this study collection. (See the commentarial images to A10 for various depictions of Mulian and a brief excerpt from Mair's translation of the Mulian sutra.) Stephen Teiser summarizes the story of Mulian as follows:

The audience knows from the start that Ch'ing-t'i has been reborn in the deepest of all hells, Avici Hell, where she suffers retribution for her evil deeds in a previous life. The focus of the drama, however, is on Mu-lien's journey, in the course of which the purgatorial hells of popular Chinese religion are described in terrifying detail. Mu-lien meets the great King Yama, Ti-tsang (Skt: Ksitigarbha) Bodhisattva, the General of the Five Paths, messengers of the Magistrate of Mount T'ai, and their numerous underlings. He shudders at the sight of ox-headed gaolers forcing sinners across the great river running through the underworld, and the prospect of people being forced to embrace hot copper pillars that burn away their chests induces even greater trembling and trepidation. The tale is nearly at an end by the time Mu-lien locates Ch'ing-t'i in Avici Hell, her body nailed down with forty-nine long metal spikes. At this point the Buddha intervenes, smashing down prison walls and releasing the denizens of hell to a higher rebirth.

It is also in the last few scenes of the tale that yü-lan-p'en [i.e. the ghost festival] enters explicitly into the story. Ch'ing-t'i has been reborn as a hungry ghost endowed with a ravenous appetite that she can never satisfy due to her needle-thin neck. In fact, Mu-lien tries to send her a food offering through the normal vehicle of the ancestral altar, but the food bursts into flame just as it reaches her mouth. To rescue her from this fate, the Buddha institutes the yü-lan-p'en festival: he instructs Mu-lien to provide a grand feast of "yü-lan bowls" on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, just as monks emerge from their summer retreat. The Buddha prescribes this same method of ancestral salvation for other filial sons to follow in future generations, and the story ends with Ch'ing-t'i's ascension to the heavens.

The Mulian narrative provides a great deal of direct imagery for the hell scrolls (and perhaps vice versa), from copper pillars to Yama, from ox-headed gaolers to the Magistrate of Mount Tai. Yet its connection with these hell scrolls doesn't end there, and Qitao Guo in his Ritual opera and mercantile lineage describes the "Mulian operatic series" (Mulian liantaibenxi) as follows:

Besides the current three-volume version, which is called the "formal opera" (zhengxi) as it is about the Mulian story proper, there were nine additional volumes about popular legends, such as the Tripitaka's journey to the West, Guanyin, and Yue Fei.

Guanyin, Yue Fei and Taizong (the last whose visit to hell is recorded in Tripitaka's Journey to the West) together with Mulian actually constitute the four most common narrative influences in these hell scrolls judging by the number of their appearances.

Mulian rescues his mother in hell in scroll G02. For other examples, see A10, B09, J08, K06, M01 and S15.

2. Yue Fei and Qin Gui both have their fortunes reversed

The Story of Yue Fei was often performed alongside the Mulian opera, and along with other such historical epics and supernatural tales became a new operatic genre in the Yuan-Ming transition.

In the 12th century, General Yue Fei was a daring leader and successful campaigner, ever loyal to the Song Dynasty. Yet the Song court eventually wanted to appease the Jin Dynasty that had pushed it southward, and the court had to collar Yue Fei. Yue Fei ended up in prison, and the Song court's Chief Counsellor Qin Gui had him poisoned. Twenty years later, the court (suffering from a bout of patriotism) posthumously pardoned Yue Fei, and soon after that, the Yue clan was rehabilitated and enjoyed new esteem. That led to Yue Fei's grandson compiling various semi-historical mythic elements about the general into a narrative, or as Frederick Mote describes it:

These include the remarkable stories about his birth and his mother’s ingenious rescue of the one-month-old babe and herself in a flood, his father’s instructing his son in classical and military texts, and his mother, at some unspecified moment in his life, having tattooed four large characters on his back, jinzhong baoguo 盡忠報國 meaning “requite the state to the limits of loyalty.” That element of the myth is particularly hard for some recent scholars to abandon; they see it as the directing theme of his entire life….

Those four characters appear on the flag above Yue Fei's head in scroll A06 in this collection. Yue Fei gradually becomes the god of loyalty, and later state shrines are erected on his behalf during the Ming. Conversely, Qin Gui becomes villified, and nowhere so much as in these hell scenes where he appears before the judge in at least seven scrolls. (That number rises to ten because one easily recognizable scene of a balding, pointy bearded man being marched before the magistrate with a sign tied to his back is sometimes labeled Qin Gui, sometimes not.) Qin Gui's wife, the "gossipy Mdm. Wang," is also sometimes portrayed in transit through hell carried in a cage. Both the stories about Yue Fei and Qin Gui allude to postmortem justice and hence a suitable topic for the hells.

As an aside, this story of a man unjustly poisoned for his loyalty to the state when barbarian armies were moving in, only to be recompensed in reincarnation and later to become a god is found in other Song Dynasty narratives such as the Wenchang tale. As Terry Kleeman translates this god's autobiography:

One day an emissary came with a gift of (poisoned) wine, which I accepted with a bow. When I had finished drinking, there was a second message, saying that I had “exhausted loyalty in service of the state” 盡忠於國. From the first I did not allow my single death to disrupt my perfect composure. But I still was worried that the way of the Zhou house was in decline and that the foundation of civil and martial virtue had been lost.

Even the four characters are almost identical to that of Yue Fei. I simply note this overlap to highlight the fact that we are dealing with a pool of images that can be shared by multiple narratives. Such is also the case with Mulian whose story line gets appropriated by other heroes such as Dizang and Wuxian (see below).

Qin Gui led before the underworld magistrates in scroll S14. For other examples, see A06, B06, C04, L02, M02, S09 and S17.

3. The iconic Guanyin (a.k.a. Guanshiyin)

Guanyin's locus classicus is the Lotus sutra in which this bodhisattva, known in Sanskrit as Avalokitesvara, is marked by his intense compassion and ability to save anyone who calls out to him. This compassion even extends into hell as recorded in that sutra's gatha, and Burton Watson translates the relevant verses as follows:

Throughout the lands in the ten directions there is no region where he does not manifest himself. In many different kinds of evil circumstances, in the realms of hell, hungry spirits or beasts, the sufferings of birth, old age, sickness and death - all these he bit by bit wipes out.

In Chinese Buddhism, Guanyin gradually became feminized and grafted onto Chinese narratives. For example, early 14th century stories depict Guanyin being born as Miaoshan 妙善, a pious daughter to a cruel king. Angered by Miaoshan's choice to live a life rather like that of a Buddhist nun rather than marry, the king ordered her to be taken to the execution ground, but a tiger came to the rescue. As Glen Dudbridge translates:

The tiger carried Kuan-yin along for a thousand li, then set her down in a forest. At first she remained unconscious. She dreamed that two boys in black led her on a tour of Feng-tu, the Underworld. She met the one they call Yama, who received and attended her with the greatest respect. She also saw all the sinners, dismembered, burned, pounded and ground up, receiving their fill of suffering. Then Kuan-yin recited sutras on their behalf, so that they were delivered.

In later versions, Miaoshan doesn't merely dream of hell but dies and goes to hell directly. In still later theatrical portrayals, the stage directions call for her to leave the execution ground on the back of the tiger - an icon often associated with Guanyin - and they direct the supporting actors to dance and play the demons and spirits who bring her to hell and to Yama.

Even though Guanyin is connected to hell via traditional Chinese narratives, her presence in the hell scrolls may be more as an icon than as a narrative allusion. That is, unlike Mulian and Yue Fei who are generally defined by their background stories that are explicitly referenced in their images and inscriptions, the Guanyin background story per se is largely absent here, and the scrolls may instead evoke her pervasive symbolism of compassionate salvation more than anything else.

Guanyin on her tiger in scroll I03. For other examples, see E01, J09 and M01. For a scroll dedicated solely to honoring her, see S19.

4. Emperor Taizong faces charges in the underworld

Much has already been said about Li Shimin or Tang Emperor Taizong, for whom this study collection is named. (See scroll A01 and his commentarial hotspot there.) The Dragon King of the Jing River had offended the Jade Emperor and sought protection from Tang Emperor Taizong, and while the latter initially rose to the dragon's defense, through no fault of his own he unable to prevent the dragon from being beheaded. This turn of events heavily weighed upon Taizong, or as Anthony C. Yu translates the tale in The journey to the West:

He was sleeping fitfully when he saw our Dragon King of the Ching river holding his head dripping with blood in his hand, and crying in a loud voice: "T'ang T'ai-tsung! Give me back my life! Give me back my life! Last night you were full of promises to save me. Why did you order a human judge in the daytime to have me executed? Come out, come out! I am going to argue this case with you before the King of the Underworld." He seized T'ai-tsung and would neither let go nor desist from his protestation.

The dragon only lets go after Guanyin herself (see above) intervenes, but over time, Taizong's illness and delirium only get worse until he does indeed appear before the judges in hell. Taizong pleads his case before Qin Guang, magistrate of the first court (which is where he usually appears in these scrolls), but the judge assures him the dragon has already been sent to reincarnation via the tenth hell's wheel-turning platform. The judge not only lengthens Taizong's own life (literally at the stroke of a pen), he also lets Taizong tour through the underworld to learn of the eighteen hells and the tortures they contain. As in the Mulian sutra outlined above, the tortures, demons, bureaucracy, geography and karmic mechanics described in Taizong's narrative are visually replicated in the hell scrolls. His tour survives not only in The journey to the West but also among the texts excavated at Dunhuang. (See Arthur Waley's Ballads and stories from Tun-huang.)

Taizong accompanied by the headless dragon is depicted seven times in these hell scrolls, and the full impact of the Taizong story on hell imagery is exemplified by the first scroll of the Vidor collection that assures the viewer how the pictures are based on Taizong's visit to the underworld and not on the artists' own imagination.

Taizong and the beheaded Dragon King in scroll D01. For other examples, see A01, K05, L05, M02 and S21.

5. "Liu Quan delivers melons"

In five scrolls, a man is seen presenting a basket of melons to the underworld magistrates. Also recounted in The journey to the West, this story begins with Taizong, while touring hell, learning how the ten kings were partial to southern melons. Taizong promises to send them some, and after he returns to the yang world of the living, he seeks out a volunteer to make a delivery to the yin world of the dead. Depressed because he had accidentally driven his wife to suicide, Liu Quan steps forward to make the delivery. With a basket of melons on his head and poison in his mouth, he descends into hell, delivering the produce to Yama himself. The hell kings richly tip the delivery man, both reuniting him with his wife and eventuallly returning them to life.

Liu Quan delivers southern melons to the hell magistrates in scroll L03. For other examples, see B03, I03 and M01.

6. The treasonous Empress Lü of the Han dynasty

Appearing three times in this scroll collection, Empress Lü attempted to usurp the empire for her own family after Gaozu, her husband and founder of the Han dynasty, had died. She is depicted beside other rebels against the Han such as Ying Bu 英布 who led a revolt in 196 BCE that was suppressed by Gaozu, or she is portrayed beside her victims such as Han Xin 韓信, who had uncovered her plans only to be executed by her, or Peng Yue 彭越, whom she falsely charged with insurrection even though she had originally agreed to assist him in certain court matters. In these scrolls, Empress Lü's legendary disloyalty to the dynasty may serve as a counterweight to Yue Fei's legendary loyalty.

Han Empress Lü and Peng Yue whom she betrayed in scroll S10. For other examples, see L01 and M02.

7. "Dizang rescues his father"

The narrative of "Dizang rescuing his father" 地藏救父 appears only once in the scrolls, and I am having difficulty tracking down its origin. The bodhisattva Dizang endeavors to bring an element of mercy to hell - for his images, see the commentary to scroll A05, and for his underworld role, see the webpage on mercy and respite. According to the Sutra of the past vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva which was already well known by the 10th century and became the core text of the Dizang cult, in two of his previous four lives he rescues his mother out of filial obedience, not his father. As Heng Ching translates the vow:

May my mother be eternally separated from the hells, and after these thirteen years may she be free of her heavy offenses and leave the Evil Paths. O Buddhas of the Ten Directions, have compassion and pity me. Hear the far-reaching vows which I am making for the sake of my mother. If she can leave the Three Paths forever, leave the lower classes, leave the body of a woman, and never again have to endure them, then, before the image of the Thus Come One Pure-Lotus-Eyes, I vow that from this day forth, throughout hundreds of thousands of tens of thousands of millions of kalpas, I will rescue living beings who are suffering in the hells for their offenses, and others of the Three Evil Paths. I will rescue them all and cause them to leave the realms of the hells, hungry ghosts, animals, and the like. Only when the beings who are undergoing retribution for their offenses have all become Buddhas will I myself accomplish the right enlightenment.

As Zhiru in The making of a savior bodhisattva: Dizang in medieval China summarizes, "By representing Dizang as a filial daughter in two of his past lives, the scripture harmonizes two paradigms circulating in medieval Chinese society: the bodhisattva and the filial child." How it came about that Dizang instead rescues his father in more recent times is still uncertain. Regardless, this act of filial piety became popularized, and according to Wolfram Eberhard, the Ming drama Hualong hui refers to Dizang in a story very much like that of Mulian rescuing his own mother (above). Some traditions indeed have Mulian becoming Dizang.

Dizang rescues his father in scroll M02.

8. "Wuxian rescues his mother"

Also occuring only once in the scrolls, "Wuxian rescuing his mother" 五顯救母 apparently refers to yet another Ming drama, or as Qitao Guo in his Exorcism and money: The symbolic world of the Five-fury spirits in late imperial China summarizes:

In the late-Ming novella Journey to the South, Huaguang, called Wuxian Lingguan Dadi 五顯靈官大帝 (the Great Thearch and Divine Agent of Five Manifestations), appears as an impudent troublemaker whose intemperate and wanton mischief prompts the Jade Emperor to banish him repeatedly to earthly exile. But this Huaguang is also given a noble side in the same novel. He distinguishes himself as a paragon of filial piety; and like Mulian, he embarks on an epic journey to rescue a human mother from the depths of the underworld.

Guo highlights the fact that many of these stories become conflated and that Wuxian himself becomes somewhat interchangeable with other god-like figures by the names of Wuchang and Wutong.

* * *

The scrolls allude to other narratives but, with the exception of the story about Pan Cuiyun and Weng Zhengchun (which I have been as yet unable to identify), none are referenced more than once in the collection. Sometimes there are implied narratives such that behind the creation of the Pure Land, often the destination of the worthy in the first scrolls, and indeed Amitabha, founder of the Pure Land through his intense mental concentration, is directly referenced in A10. No doubt this list of narratives will grow over time, but the above tales are the principal sources for medieval and late imperial notions of hell.

Wuxian rescues his mother in scroll M01.