|

The Rhodes and |

Interview preparation |

|

A personal note: As a friend came down from the interview room, she described the layout to me as looking like "The Last Supper." It rather felt that way, too. As I was led up the steps to that final interview, I recited my planned mantra -- deep breath, stand up straight, smile, look them in the eye. And yet I had fun -- nervous, trembling, risky fun -- but fun nonetheless.

Preparation

- Know your benefactor. Read a biography on Cecil Rhodes, do a bit of research on the Marshall Plan, know why Mitchell matters to Ireland, be familiar with Gates' vision of Cambridge.. While you are reading them, look for any parallels with, direct application to or remote echoes of your own "story." (I had a journalism degree and found out that Cecil Rhodes had interesting views on journalism.) On one hand, it may never come up in the interview, but you will have a sense of security knowing "that base is covered." On the other hand, a Marshall regional chair admitted that he always asks the candidate about what they know of the Marshall Plan.

- Be up on the news. Some U.S. universities recommend habitual reading of the New York Times in the summer prior to the interviews. For example, you may have on your transcript a class in Chinese modern history. If an event has recently taken place there, the interviewers might ask you about how you view that event via your coursework. (In a Rhodes final round, I once asked a journalism major who also studied Chinese religion about recent Chinese coverage of the Falun gong mass religious movement. In the ensuing silence, crickets chirped and a lone tumbleweed rolled through empty streets.)

- Past successful candidates have said that they had their friends interrogate them at length over their application materials. They even claimed those to be the most difficult interviews they had to endure. Everything is fair game for intense grilling.

- Be sure to re-read your transcripts before the interview. If there is an out-of-place grade on it, that's obviously fodder for a question. If there is a course there that seems well outside your specialization, you might be asked how you as a chemist responded to Crime and punishment or how a linguist can contribute to a discussion on evolutionary theory. Also be sure to re-read your application and try to see it as a third-party might.

- Mock interviews are becoming increasingly common, and some U.S. universities strictly parallel the Rhodes structure of a dinner/reception the night before and set interviews the next day. Some universities go so far as to check clothes, advising male students to carry two shirts lest soup spilled the previous night is worn to the morning interview. (Excessive, yet good advice.)

- Reed will carry out mock interviews for you, which candidates generally regard as highly useful. (One Portland institution on the other side of the river offers its candidates no less than five mock interviews! I worry that one can become too polished and mechanical, but it works for them.) The interviewers may be instructors or trustees whom you do not know, and the questioning should be academically rigorous but friendly. (Often the mock interviews are more fearful than the actual interviews because the former are trying to push you to the limits to see how you can improve before the latter.)

Interview structure

- (Many of these notes are only applicable to the Rhodes.)

- As noted above, there is often a reception the night before the interviews or a lunch if the interviews are beginning in the afternoon. Officially, it is not part of the selection process, but everyone is naturally on pins and needles. (One gets suspicious with the prearranged seating and the judges on signal get up in the middle of the dinner and switch to new prearranged seats.) The selectors are understandably curious as to how you interact with your fellow candidates -- did you politely hear them out and then respond, or did you monopolize the discussion? Did you kindly solicit information from someone who seemed to be saying very little, or did you leave the status quo as it was?

- DO NOT DRINK, even though alcohol will be available. (I have heard this comment from several sources.)

- Do not merely engage the interviewers -- talk to the rest of the candidates as they often have interesting stories to tell. Ask questions.

- You must provide your own accommodation that night although the Rhodes Foundation may have arranged for a discount rate at a nearby hotel. In the morning, all candidates (on state and regional level) are kept together in a room as the judges interview the candidates (usually "upstairs") one by one. The common room can be the scene of cards and Trivial Pursuit, and surprisingly, the atmosphere is light-hearted. The candidates will dine together, and in the mid afternoon, the judges will continue to deliberate, sometimes inviting a candidate to come back and answer a few more questions. (Second interviews indicate absolutely nothing.)

- The winners are announced to all the candidates at the end of the interviews.

- Super candidates from time to time win both the Rhodes AND the Marshall scholarships, and I know Reedies who suddenly found themselves in this "awkward" situation. Yet you can't have both. Over the years, the Rhodes and Marshall foundations have experimented with the timing of their interviews to prevent a tug of war, but I'm not certain if this problem has been satisfactorily resolved. In years past, a Rhodes Scholar was immediately asked whether he or she would accept it, whereas a Marshall Scholar was given a few days. There are no alternates chosen for the Rhodes Scholarship whereas there are for the Marshall. The Mitchell is a bit harsher in that accepting a final interview commits the candidates to accepting the Mitchell if elected. Interviews for all three tend to be around mid-November or just after.

Types of questions

The interview is not necessarily the most important part of the whole process; some Rhodes selectors consider it a means of seeing whether the person actually reflects the documents. Both Rhodes and Marshall interviewers aspire to see how you think, and it is hoped the interview will encourage you to stop and reflect when confronting something new. For example, when the questions shift to something completely different, a good candidate might still be able to draw a connection between the seventh question and the third. Think of it as participating in a good discussion rather than a back-and-forth Q&A, and endeavor to construct logical arguments on your positions and goals during the interview itself.

You might always have an opening and closing remark in mind -- no more than thirty seconds -- just in case the need arises. For example, some scholarships typically begin, "So, tell us a bit about yourself." And they often end, "Do you have anything you would like to add?"

Don't rush your answers. It's fine to pause a moment for thought. Once you've answered -- and keep the answers concise but thorough -- be quiet and wait for the next one.

Don't rave about your accomplishments. It's already in the application.

The Marshall interview is intended to be "rigorous but not confrontational." If there is no specialist in the candidate's field, one of the interviewers will research it in advance. Short responses -- even one word responses -- are good, as is a bit of humor and a bit of nervousness. The candidate may be interrupted while giving an answer, and this may simply be intended to see how fast the candidate reacts to a new situation. And it is important to say "I don't know" if necessary. There is no shame in that. They want to see if you will hold onto your ideals but not be so dogmatic as to not budge an inch. Otherwise they will pursue you into rougher and rougher waters. If you feel you didn't answer something well, don't let it fluster you. You probably answered other questions better, so just move on.

The interviewers will be a mix of past scholars and non-scholars, of academics and professionals. Sometimes the interviewer list is published in advance.

A regional Marshall chair detailed the pre-arranged structure of the interview as follows:

- The first question is a "fluff area," just to set the candidate and the interviewers at ease.

- The second interrogator will be the principal interrogator, questioning at length on the candidates field of specialty.

- If you state an opinion, you may be asked the source of your opinions. You may be asked to recommend further reading on a key issue.

- They then proceed in an order, each focusing on one issue. For example, if you have just started an economics class, an economist might ask you about interest rates in the U.S. to see how they might affect Japan. The point is not to get at the student's knowledge but more to see how the student thinks.

- One questioner may go for a quick fire round, asking you for your favorite book, your knowledge of who is the current Secretary of the Interior (if the candidate is a student of politics), what a particular Latin phrase means (if the candidate is a classicist), what the candidate's favorite Shakespeare play is (if the candidate in her freshman year took a course on Shakespeare plays), etc.

- Q: Who is X? A: Don't know. Q: Who serves in position Y in the U.S. government? A: Not sure. Q: If you were to guess . . . . A: X? Q: Good.

- An exchange like the above is simply to see if the candidate is simply answering questions or actually thinking about what is going on. Yet while I've heard Marshall administrators say this approach is indeed employed, I have yet to hear anecdotal evidence that such was the case.

- The candidate is frequently asked, "What will you do if you don't get the scholarship?" (As one Marshall selector has said, an answer of law or med. school lets the wind out of the sails.)

- The last question sometimes concerns what the candidate knows of the Marshall Plan.

- This interrogation is usually scheduled for twenty minutes but may take longer.

- (I have a list of other questions frequently asked, but of course those will be saved for your mock interviews!)

At a recent conference, selectors from seven or eight national scholarships (including the Rhodes and Marshall) were asked about common mistakes made during interviews. They listed the following five:

· Candidates would use the words "never" and "always." That simply opens oneself up to a forced withdrawal.

· Candidates were falsely confident. It is fine to be phased; it is acceptable to be a bit embarrassed.

· Candidates refused to say "I don't know."

· Candidates would attribute everything they knew on a given subject to a particular book they read in a particular course. In such cases, "you" disappear, and the book takes your place.

· Candidates take the interview as an exercise in defense rather than discussion. At an extreme, candidates even get defensive when something about their application or personal statement is under examination.

For specific examples of questions, see the "Past Reed candidates speak" section of this website. The Gates website on interviews is very specific in terms of what questions are asked, and while they are more focused on whether the applicant is a good Cambridge fit (rather than being focused on his or her past endeavors), it's a good list of questions to ponder and to prepare for any scholarship.

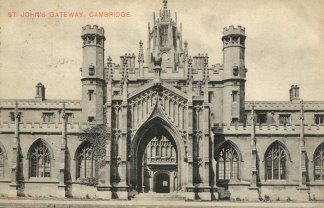

St. John's College gateway to the rear courts, Cambridge |

|

||