|

The Gates |

Advice to Reed applicants |

|

Eventually to rival Oxford's Rhodes Trust in number of scholars and

amount of financial coverage, the new Gates Cambridge Scholarship describes its

beneficiaries as follows:

These individuals will combine academic excellence with leadership potential, and a commitment to serving their communities.... In selecting Gates Cambridge Scholars, the Trust seeks students of exceptional academic achievement and scholarly promise for whom further study at Cambridge would be particularly appropriate. Students will need to provide evidence of their ability to make a significant contribution to their discipline, either by research, or by teaching, or by using their learning creatively in their chosen profession.... The Scholars are thus expected to use their education for the benefit of others and to show commitment to improving the common weal.

During a trip to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in Seattle, we had the opportunity to meet with Gordon Johnson, Provost of the Gates Cambridge Trust, and so we have the opportunity to flesh out some of its intentions and stipulations.

Feeding your "intellectual demon" at Cambridge

The Trust seems to seek two basic qualities, namely scholarly fervor and a proper fit at the University of Cambridge.

As for scholarly fervor, Johnson described it as students possessing an "intellectual demon." "They want to make something of their lives," he said, "but they also want to do something." The Trust's basic goal is to develop leaders who will improve the circumstances within and without their countries. Yet it should be noted up front that, despite the wording of some of the Trust's literature, this desire "to do something" is not intended to limit applications to those people with obvious humanitarian and outreach interests. When asked if, for example, a student devoted to ancient China could apply for a Gates Cambridge Scholarship, Johnson emphatically answered that such a student would be an excellent candidate. (Johnson himself is an historian of the Indian subcontinent.) Evidence of intellectual demon possession begins with standard scholarship parameters -- a GPA of 3.7+ (although the Trust will take into consideration Reed's anti-inflation grade policy), strong letters of recommendation (including one focused on the candidate as a person and not only as a student), and meeting the requirements for normal Cambridge admission (see below). The Trust also looks for examples of doing something quite difficult in one's undergraduate degree as well as breadth of scholarship beyond the elementary stage. For examples of the last point, a hard-core philosopher with third-year calculus or a scientist who pursues a third- or fourth-year language demonstrates such breadth and intensity. The trust also seeks students who have not yet peaked and who can step back and ask themselves the questions "Why am I seeking this knowledge? What use is it?"

As for being a proper fit at the University of Cambridge, this quality requires a bit of homework. Candidates must find out about Cambridge and its courses, and they must have good, specific reasons for wanting to study there. For example, Cambridge may have a renowned specialist with whom the student wants to work, or it may have a particular course of study that best fits the candidate's future endeavors. The Trust does not want students merely intoxicated by Cambridge's traditions and dreamy spires. Also, the Trust does not want students who are not yet ready for Cambridge coursework. That is, a certain amount of knowledge is assumed for graduate degrees, and Ph.D. research sometimes takes for granted that all taught coursework has been completed. There is much less day-to-day structure at Cambridge, although for taught courses (i.e. second undergraduate degrees and some master's degrees) there will be lectures and tutorials. Even then, a Cambridge student is expected to have a great deal of initiative and passion for his or her studies. The intellectual demon is in itself part of being properly suited to Cambridge.

The scholarship award

Founded in October 2000, the Trust now seeks out ninety scholars a year from all over the world (but a substantial block earmarked for the United States) at any given time. It will finance tuition, maintenance and some extra expenses for Cambridge study lasting one to three (and in rare cases, four) years. This flexible duration can thus cover anything from one-year master's degrees to longer Ph.D. degrees or even combinations of these degrees. It does not extend to undergraduate degrees. The Trust's flexibility even extends to allowing students to change programmes while at Cambridge if it is necessary and if the Trust approves. For details of the award, go to the Gates Cambridge website which also has links to the relevant Cambridge University resources you will need to access.

The scholarship process

While the Gates Cambridge Scholarship bears a resemblance to the Rhodes and Marshall programmes, the process itself is rather different. In essence, a student applies to and is accepted by Cambridge first and then is entered into competition to become a Gates scholar. On the surface, it may sound more daunting than applying for a Rhodes or Marshall, but in fact the accepted application at Cambridge eliminates many of the traditional scholarship steps when pursuing the Gates. The application process to Cambridge is like that of many other universities, and Cambridge not only accepts and rejects applications, it ranks them in order of preference and passes those ranks to the Trust. Thus if the candidate's Cambridge application is strong -- if the candidate makes a solid case for becoming a desirable student at Cambridge -- it greatly assists the candidate's application for the Gates scholarship. Cambridge University provides a useful website on postgraduate studies there, and in its application form, there is space for about two paragraphs to give details as to why the candidate wants to study at Cambridge. Applicants sometimes leave the space blank or fill it in with non-viable or vague statements. They miss a major opportunity to provide a clear, concise account of why their study at Cambridge is reasonable and necessary. The Gates form will allow applicants to expand upon this statement in a 500-word essay.

So once the applications are in, the applicants are either accepted or rejected by the university or by the colleges, and those that are accepted are ranked. The Gates Trust then takes a healthy percentage of the top-ranked applicants and in January or February gathers them together for interviews. (In past years candidates from the United States met in Annapolis.) The Trust organizes interview panels focused on the candidate's general field -- e.g. a science interview panel or a humanities interview panel -- and each interview is about 25 minutes in duration.

Interviews may begin generally, such as "Tell us what is interesting or exciting in your studies," then perhaps continuing on to the question "Why do you want to pursue that subject in Cambridge?" (Note these two questions are pursuing the two basic qualities -- possession of the intellectual demon and best fit at Cambridge -- discussed above.) The questions then become more detailed. The interviewers seek to understand the candidate's attitudes, level of maturity and character. For example, they do not want to see volunteer work that seems to be done just "to tick off that box" in a curriculum vitae. In other words, genuine character matters. "We start at the Angel Gabriel and go up in terms of quality of character," Johnson quipped.

Even at this stage, the Trust must remain rather flexible in terms of process. Some Cambridge departments have late deadlines when it comes to deciding on successful applicants, and the Trust endeavors to solicit the information from them early. Furthermore, some departments discuss Ph.D. candidates year round without firm deadlines.

Thus after the initial application to the university or college and to the Trust, the candidate simply waits for an acceptance to Cambridge and an invitation to a single interview. After that, an offer is made to the successful candidate. No alternates are selected.

Reed's role

There is no formal role for the candidate's institution to play in this process. There is no limit to the number of Reedies who can apply, nor is there an institutional endorsement. As it is an international scholarship with no set country-for-country quotas, "residency" is not an issue. The Trust will not even inform Reed as to who applied from the college or who received an interview. In other words, the ball is completely in your own court. Yet on an informal level, please remember that the committee is always willing to help you if you want its help -- reading drafts, making editorial suggestions, arranging mock interviews. Reed has Cambridge graduates (including myself) who can tell you about the university and its colleges and who can perhaps suggest ways of making personal contact with Cambridge instructors and lecturers. (Johnson encourages candidates to make such contacts, and these contacts can suggest programmes, colleges and advice as to whether Cambridge is a good fit. That contact, if it is sufficiently close, can even develop into a useful letter of recommendation, he said.)

Vocabulary

Below are a few terms used by the Gates Trust or by the University Prospectus that may require a bit of elucidation. Please let the Fellowships and Awards Committee know if you find other terms that need clarification, and the list will be expanded.

Affiliated student |

An affiliated student is a student who already has a bachelor degree but then pursues a second bachelor degree. The Gates no longer funds bachelor degrees. (Of the four scholarships described on this website, only the Rhodes has that option, and the vast majority of Rhodes candidates no longer pursue it.) |

College |

In this scholarship process, the candidate is asked to list colleges in order of preference. How do you choose a college? The various on-line prospectuses are your best source of information. The prospectus also details each college's current balance of subjects (Arts, Social Sciences, Biological Sciences, Physical Sciences and Technology) which may be useful in your decision. Knowing the number of applicants to each college as well as their success rate might also be useful. If the candidate does not get into the college of first or second choice, the candidate is then added to a pool from which other colleges draw their future students. |

Department |

Departments are external to the colleges. With regard to the quality of individual departments, consult the list of links on the Selecting and Connecting page. |

First class or an exceptionally high second class |

Degrees were formerly graded as "firsts," "seconds," "thirds," "passes" and "fails," with the first three indicated by Roman numerals and with the vast majority of degrees ranked as "seconds." That led to the second-class degrees being divided into II.i ("two-one") and II.ii ("two-two") degrees, resulting in the vast majority of degrees now being ranked II.i. There exist various contradictory tables converting these numbers to American letter grades, but in general, a first is commendable while a third is cause for concern. The Trust instead asks for a 3.7 GPA, although the Trust is well aware that this is now an average grade at some American institutions. It is sympathetic to Reed's attempts to control grade inflation, and so there is a little wiggle room here. |

"Honours" Bachelor degree |

Almost all bachelor degrees in England are called "honours" bachelor degrees. The term does not carry much meaning any more. |

M.Phil. leading to Ph.D. |

In many Ph.D. programmes, there is a required M.Phil. portion that the candidate must first complete at Cambridge. This portion, usually a year long, may have a taught component and may end in an examination or perhaps a paper (for example, a written piece of high standard that demonstrates the ability to do original research). It is like a probationary period to be completed before the Ph.D. research can commence, and the M.Phil. material usually bears upon the candidate's chosen Ph.D. research. Candidates for the Gates Scholarship apply directly for the Ph.D. on the understanding that, like all Cambridge students, the M.Phil. portion must be passed in the process. Gates scholars need not reapply for the Ph.D. once the M.Phil. is passed. To determine whether an M.Phil. constitutes part of a particular Ph.D. programme, consult the department degree descriptions in Chapter Four of the Graduate Prospectus. Please note that there are also other types of one- and two-year masters programmes -- M.Sc., M.Litt. as well as M.Phil. -- which do not lead to Ph.D. programmes. Three years indeed sounds like an incredibly short period of time to secure a Ph.D., but keep in mind that graduate students usually have no teaching responsibilities. Also, it should be noted that extensions beyond three years can be secured, subject to approval by the Board of Graduate Studies (which requires a letter from your Cambridge supervisor). Extensions are often for an extra year (and, in rare cases, more). In some departments, securing extensions has become the norm rather than the exception. The Trust will consider such extensions on a discretionary basis, but applicants are to come to Cambridge PhD programs with the expectation of completing them in three years. |

A final (and personal) word of encouragement

Allow me (i.e. Ken Brashier, Religion Department) to slip into first-person singular. I was fortunate to take my own Ph.D. at Cambridge and enjoyed it immensely. The system is indeed very different from what one expects at a U.S. research university with both advantages and disadvantages. On one hand, there are significantly fewer taught graduate courses, and there is no caste of underpaid graduate students teaching undergraduates. My colleagues were envious of me because I already had a taught, two-year master's degree from the States with some background in my field's research methods. On the other hand, the lack of taught courses leads to great advantages as well. First, there is a great deal of freedom simply to 'get on with it,' to dive into research without the interruption of teaching or being taught. Second, my supervisor was much more available to me precisely because he wasn't always tied up teaching graduate-level courses.

Finally, Cambridge is a city of cobblestones, boys choirs, limestone spires and sinking punts -- and there is something to be said for all that. Yet more importantly, it is a center for radio telescope studies, polar research stations and new computer laboratories. Despite its old reputation as being more focused on the sciences (as opposed to Oxford, which was supposedly a bit more focused on the humanities), Cambridge covers most subjects fairly well. The newest wing of the University Library (a library that is much easier to use than Oxford's) is devoted to Asian studies, and some rather space-age looking buildings now house the law and various social science departments. Cambridge (and study in Britain in general) is NOT for everyone, but if you do your homework on the place, you might find good reasons for studying there. I think Reedies are generally well-suited for Cambridge and Oxford because of their conference experiences, their senior thesis work and the high expectations they place on themselves to do original work.

Good luck,

K.E.B.

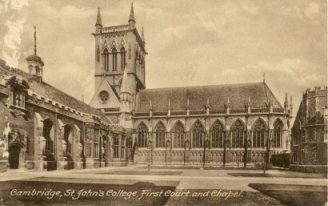

St. John's College Second Court, Cambridge |

|

||

Last updated: August 2012