Constructing Bodies of Constant Width

Consider what happens when you roll a sphere between your hands. Assuming your hands are perfectly flat and parallel, then no matter how you roll, the distance between your hands–the “width” of the sphere–should remain constant. Is a sphere the only solid for which this is true? Interestingly enough, there are in fact many solids possessing this constant width property which are not spheres! To see how, we need to be a little more formal with this idea of width.

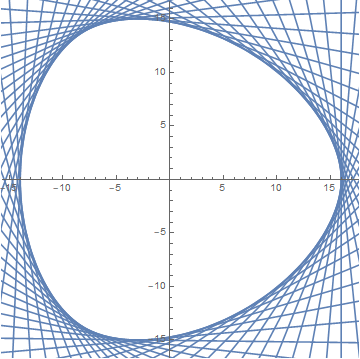

Suppose you have some compact, convex body living in . For example:

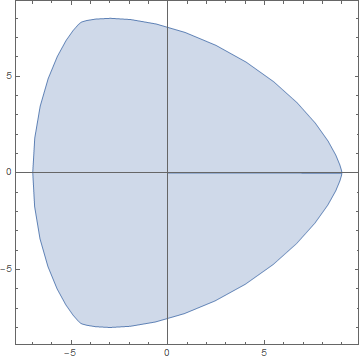

You might recognize this figure as the Reuleaux triangle.

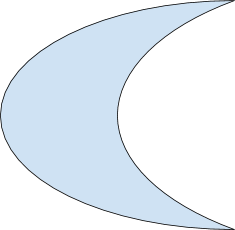

This body is not convex–you can draw a line connecting two points inside it which pokes outside.

To capture this notion of width, we want to be able to draw a pair parallel lines just touching the body in two places and find the distance between them. Notice that for any choice of unit vector, we can find a line with that vector as normal which touches the body at exactly one point. We can actually find two, since a line has two choices of unit normal vector, but we can insist that, for a given unit vector, the line we pick is the one with outwardly oriented normal (i.e. pointing away from the body, which is unambiguous since the body is convex). Thus, given a support line given by a unit normal vector , the support line parallel to it is given by . These “support lines” are analogous to our hands rolling the body around.

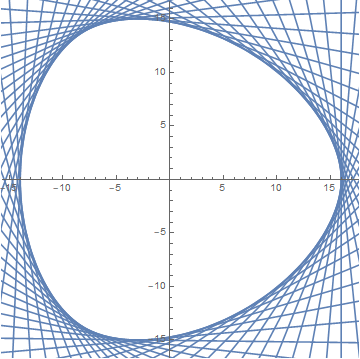

Pairs of parallel support lines given a varying unit vector angle–the distance between the lines is the width in that direction.. Note that this figure has constant width!

We call the distance between two parallel support lines with normal direction the width of the body in the direction. If this width is the same for every choice of , then the body has constant width. The usual notation is to define the “support function” which, given a unit vector, gives you the distance from the center of the body to the support line having that vector as normal. Then, constant width means that is constant for any unit vector . Note that we can similarly define bodies of constant width in any number of dimensions by defining the support function from to in general. The support lines become planes in three dimensions, and hyperplanes for .

Given any convex body, there exists such a support function. It turns out that we can also choose specific support functions and guarantee they specify a convex body. First, consider the extension of where for unit vectors in and (in particular, since is in ). satisfies a few key properties:

Additionally, has the constant width property for nonzero if and only if h also does. So, if we can find such a function with this constant width property and satisfying the above properties, then we have a convex body of constant width with support function (H restricted to the unit sphere).

One such support function (given by Fillmore 1969) is for . Note this is not defined in terms of unit vectors u, so let’s rewrite it as . (Note that and for unit , the angle it makes with the x axis is . This function clearly satisfies the first two conditions above, and the third may be checked with some algebra and the triangle inequality.

We can also see that this function has the constant width property:

Therefore, we can define a body of constant width using this support function! Here’s what the body defined by this support function looks like (for a = 15 for example):

Notice the similarity to the Reuleaux triangle depicted above—this body is an analytic version. (Choosing gives the Reuleaux triangle, and the body approaches a circle as a approaches infinity. For the body is no longer convex.)

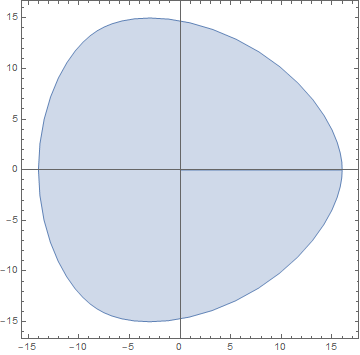

Here’s an example of a body of constant width in three dimensions:

The support function for this body is

This body is piecewise smooth and has the same symmetries as a tetrahedron. It is an example from a particularly interesting class of bodies of constant width which exhibit the symmetries of familiar solids (tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron, etc), and other subgroups of , i.e. rigid rotations of .

How exactly can we create these bodies, given one of these support functions? Recall that our definition of constant width involves parallel support hyperplanes which bound the body in every direction. These planes are exactly for all in (i.e. ).

If our support function h satisfies the above conditions, and so defines a convex body, then this body is the set of points x such that:

In other words, each hyperplane divides into two half-spaces, and the body is the intersection of each of the “interior” half spaces (the ones lying opposite the normal vectors of the hyperplanes). So, one way to create a body given a support function is to simply find this intersection. This method turns out to be difficult to implement in practice however–you would need to have your mathematical software intersect an infinite, or at least very large, number of half-spaces.

An approximation of the body using support lines. The body is the limiting intersection of the interior half spaces given by these lines.

It turns out there is a simpler approach: for unit vectors in , the gradient parametrizes the boundary of the convex body having support function (try checking this fact for yourself).

For example, if we choose as above then we have:

Now, we can parametrize this gradient with spherical coordinates and plot it using Mathematica, giving the body seen above. Next time, we’ll discuss why the function gives a body with tetrahedral symmetry, as well as how to create even more solids with a number of different groups of symmetry. Until next time!

← Back to Project Project Home