|

Rel. 361: To hell with

comparative religions Fall

2020 Syllabus |

K.E. Brashier (ETC 203) Office hours: W 9-10 a.m. and F 9-11 a.m., or by appointment, or whenever the door is open |

|

The sinner sank below us [into the boiling pitch], only to

rise Cried, "Here's no place to show your Sacred Face! Then stay beneath the pitch." They struck at him You're able to, in darkness." Then they did From their forks keeping it from floating up.[1] |

Deep-frying

the damned in pitch or oil is of course just one among

scores of horrific punishments awaiting us in Dante’s hell where we must

famously “abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” But apparently

it’s not just a 14th century Italian recipe being prepped for the

tables of hell; 13th century English and early 20th

century Chinese art independently provide their own illustrations of the same

culinary torture:

|

A

hell scene in which an individual is being forced into a three-legged caldron

of boiling oil where attendants blow through long pipes to stoke up the

flames underneath. (From

the English 13th century Getty

Apocalypse Manuscript.) |

|

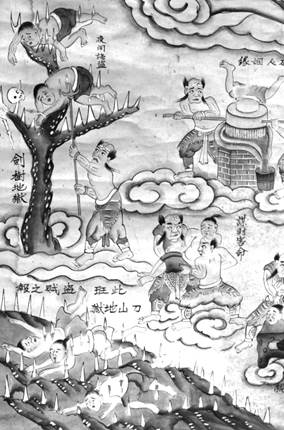

A

hell scene in which an individual is being forced into a three-legged caldron

of boiling oil where attendants blow through long pipes to stoke up the

flames underneath. (From

a Chinese early 20th century hell scroll in our collection). |

And

I could just as easily have cited textual or pictorial examples of frying the

dead in caldrons of boiling oil from Hinduism’s Markendeya sutra and Buddhism’s Devaduta sutra, from

Taiwanese accounts in which spirit mediums visited hell in 1976 and Mary K.

Baxter’s own trip to hell in that same year.

Yet

great scholars of religion such as Clifford Geertz rightly warn us against too

quickly making vague comparisons because such comparisons can be rather

useless:

There is a logical conflict between asserting that, say,

“religion,” “marriage,” or “property” are empirical universals and giving them

very much in the way of specific content, for to say that they are empirical

universals is to say that they have the same content, and to say they have the

same content is to fly in the face of the undeniable fact that they do not…. To

make the generalization about an afterlife stand up alike for the Confucians

and the Calvinists, the Zen Buddhists and the Tibetan

Buddhists, one has to define it in most general terms, indeed – so general, in

fact, that whatever force it seems to have virtually evaporates.

I am

in complete agreement with this postmodernist warning here, but in this course,

we’re not interested in a general

conception such as “religion” or “property” or even in a slightly more specific

conception such as “marriage” or “afterlife.”

This

course is instead interested in pedagogical

pilgrimages of retributive, torturous hells that are usually followed by

exhortations to inform and reform the living and, surprisingly often, by a

moment of grace manifested among the tortured dead. No matter whether the

visitor is named Muhammad or Mulian, Vipashchit or Viraf, St. Patrick

or Moses, Odysseus or Dante, the protagonist is led through the grisly horrors

of hell so that he or she can return to the living and warn them to live moral

lives. From early Indian Hinduism to modern Japanese Buddhism, from

Christianity to Islam, from Dante’s Inferno

to the current evangelical Hell House fad, this anything-but-vague phenomenon

has either independently arisen (“auto-cultural”) or broadly spread out across

the globe (“cross-cultural”). We might spend some time wondering exactly how

that happened, but first we must figure out how to safely and properly compare

this phenomenon found in so many diverse traditions.

I. The trajectory and

methodology of this course

Another

famous scholar of religions, namely Jonathan Z. Smith at the University of

Chicago, summarizes the process of comparison as follows:

1. Description is a double process

which comprises the historical or anthropological dimensions of the work:

First, the requirement that we locate a given example within the rich texture

of its social, historical, and cultural environments that invest it with its

local significance. The second task of description is that of

reception-history, a careful account of how our

second-order scholarly tradition has intersected with the exemplum. That is to say, we need to describe how the datum has become

accepted as significant for the purpose of argument.

2. Only when such a double

contextualization is complete does one move on to the description of a second

example undertaken in the same double fashion.

3. With at least two exempla in

view, we are prepared to undertake their comparison both in terms of aspects

and relations held to be significant, and with respect to some category,

question, theory, or model of interest to us. The aim of such a comparison is

the redescription of the exempla (each in light of the

other) and a rectification of the academic categories in relation to which they

have been imagined.[2]

This

tripartite process well describes the general movement of our course. Alongside

surveying comparative theory in religion (at first generally and then later via

four particular methods useful in the study of hell), we as a group will

initially spend about a month describing the Lucan hell to serve as Smith’s

first comparator. What is the

“Lucan hell”? It’s a more precise label for the Protestant hell we

generally imagine today, especially in the modern American evangelical sects:

the Christian tradition’s permanently torturous state of punishment that begins

at death for sinners, contrasted with rewards in heaven for the worthies. In

terms of the Bible, this kind of hell is first described in the “Parable of

Lazarus and the rich man” from the gospel of Luke – hence the adjective “Lucan”

– from around 85 CE, and it’s a description to which Jesus or Paul might not

have themselves subscribed.[3] We’ll frame the Lucan hell both historically, beginning with Jewish

texts that fed it and progressing through medieval times when the genre fully

developed, as well as theologically,

comparing it with modern non-evangelical traditions. With those frames in

place, we’ll read several firsthand accounts of people within the American

evangelical tradition who visited hell and survived, and then we’ll spend a

week exploring the Hell House phenomenon. Hell Houses are evangelical “haunted

houses” targeting what their founders regard as the damning vices and attitudes

of modern American life, and we will be uniquely[4]

investigating their own start-up materials, from their original scripts to

their business plans. In sum, we will fully develop both a description of the

Lucan hell within the modern American evangelical tradition as well as how

people talk about it, the categories they use, the theories they apply.

With

that first exemplum firmly in place, we will move on to our second exemplum

provided by ... you. The second half of this course is mostly devoted to the

other “pedagogical pilgrimages of retributive hell” across the world, and each

of you will devote a whole conference (and formal research paper) to describing

a second example. Now you yourself will be the specialist, having chosen and

researched another tradition’s hell looking for similarities and differences, suggesting new avenues

of inquiry or questioning conclusions through comparison. As noted above, these

pedagogical pilgrimages potentially range from ancient India, to medieval

Japan, and to (non-evangelical) modern America. Now is your chance to fully describe and contextualize both another set of

primary sources about hell as well as the subsequent scholarship talking about

that hell. (I will provide you with a list of fifteen similar pilgrimages for

which I can direct you to existing research, but you are welcome to find your

own.)

You

will no doubt find striking similarities between the Lucan hell and your chosen

hell, but (I hope) you will also run into places where the terms we used to

describe the former are a poor fit for the latter. That’s where you must think

hard about comparison, its value and the new questions inspired by comparison,

and that’s where it may be necessary to rectify the categories that define our

general notion of “hell.” That’s Smith’s last step, and that’s the focus of

your final paper.

|

|

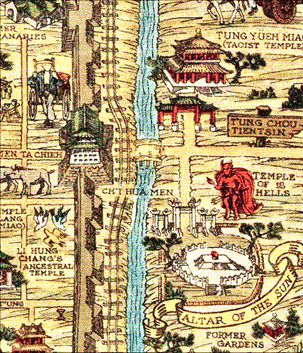

I recently

came across a 1936 tourist map (by Frank Dorn) of Beijing, China, a portion

of which is to the left. What’s ... odd

... about this picture, and why is it relevant to this course? |

II. Requirements

1.

Active and informed conference participation. Please note that active participation every day is

intrinsic to this course, and please be fully prepared for each conference,

preparation consisting of both reading and thinking about the materials.

(Your full preparation really helps me out a lot and makes conference much more

pleasant all around. We are few in number, and so it

makes a big difference to have everyone engaged.) Appended to this syllabus are some

suggestions on conference dynamics, and if conference isn’t going well, please

talk to me. We will endeavor to remedy the situation with concrete changes. I

seek your comments and take them very seriously. At the very least, I recommend

every day honing in on a particular passage that

“speaks” to you, that gives you insights and leads us to good group

discussions. I much value close reading, and I love it when we jump from

passage to passage, developing a conference theme that draws on the textual and

material evidence at hand.

2.

Four exploratories (1 page, single-spaced).

In many weeks, you will be asked to contribute an original exploration

relevant to the materials we are handling. Your chosen themes are intended to

be conducive to thoughtful analysis, and your concise answer is due at 7 p.m. on the evening prior to the

day they are discussed via e-mail. Please embed your exploratory in the

body of the e-mail and not as an attachment, and please bring a hardcopy to the

discussion so you can reference it. The first one or two may seem daunting, but

your predecessors have told me that they got a lot out of the process,

including much freedom for exploring particular issues

that interested them. Appended to this syllabus are suggestions as to

constructing an exploratory.

3.

Project proposal.

Already in the first week, you ought to be thinking about which tradition’s

hells would most interest you in your semester-long research project. This hell

might be within the tradition you see yourself studying the most in your Reed

religion courses, or it can be a chance to study a tradition totally new to

you. You will have a chance to present your proposal to your colleagues (and

they may be able to help you with suggestions in things that they themselves

have come across), and the formal proposal (in the form of a short, three- to

five-page paper) is due on 21 September in conference.

4.

Leading a conference discussion on your chosen hell. In the second half of the semester, you will be leading an

entire conference discussion on your chosen hell. You will assign us readings –

usually a primary source on someone’s visit to that hell – and you can organize

our conference (and our preparations for that conference) in any way you think

will produce the most educational discussion. (I intentionally repeated the

word “discussion” three times [now four times]. By all means

lead with a prepared statement, but please make sure you’ve planned an

interactive experience.)

5.

Description paper.

This first formal six- to eight-page paper will “describe” your chosen hell

(including how scholars talk about that hell) in the way J.Z. Smith outlines

above. The due date is prior to your

conference discussion on that hell. For example, the 19th century

Italian theologian John (Don) Bosco experienced an intense hell dream that he

narrated and Arthur

Lenti (p. xlvii) in his introduction to Bosco’s dream

wrote that “the dream must be examined and compared with the context in which

the dreamer lived ... in our case, with Don Bosco’s social, philosophical and

theological ideas: the books he read and wrote; his educational, catechetical

and pastoral endeavors at the time, events involving the Salesian Congregation,

the Church and society at large, and much more.” This is the kind of context I

(and J.Z.) would like to see in your second paper.

6.

Comparison paper.

This second formal six- to eight-page paper will compare your hell to the

modern American evangelical hell, our “anchor” hell that we studied in the

first half of this semester. Please concentrate on both similarities and differences, and consider what J.Z. Smith above said about

rectifying the categories we use when making comparisons. This paper is due at

noon, 12 December, and please include a self-addressed, stamped envelope if you

want comments. (“Just return it to my Reed box” isn’t enough, both because I

won’t be on campus over the break and because I’d rather get comments back to

you while the semester is still fresh in your memory.)

I

will provide you with plenty of materials to help you in your research,

including a “Hell starter kit” of suggested initial primary and secondary

sources for your chosen hell and a guide on how to write project proposals. I

also have a large personal library on hell traditions across the world, and so

I can loan books to you if you can’t find them in the library or on Summit.

III. Content warning

When

I was little, my mother strongly forbade me to even say the word “hell,” although I’m certain she meant I was not to

utter it as a profanity.[5]

Yet my best friend’s mother was named “Helen,” and so I would undergo

excruciatingly complex circumlocutions just to avoid ever saying her name. It’s

sometimes hard to understand the logics and discomforts that inform our avoidances.

This

course will handle a great deal of uncomfortable material. It’s hell, after

all, and people are not only going there for lots of heinous crimes, they are

also being consigned there by people making judgments about things you yourself

might not consider crimes. We won’t just encounter punishments for murder,

theft, adultery, arson, disbelief and even being too gossipy; we will also

occasionally encounter express homophobia, the graphic damnation of abortion

and the condemnation of any religious belief other than that tradition’s own.

Occasional discomfort may be unavoidable, but it’s

okay to be uncomfortable and stretched from time to time as long as it never

gets to the point of disrupting the educational process. College is all about

encountering facts and opinions that you yourself don’t already hold, and I’ve

just come to accept that not everyone thinks the way I do. If our conference

discussions become too personally

uncomfortable, I suggest quietly leaving the room for a bit, and I’m always

happy to talk with anyone about such issues outside of conference so that it

never becomes too awkward. (Other moments of discomfort might include, for

example, texts that spell out G-d or even physically picture Muhammad,[6]

acts which some of us may find offensive.) While hell tortures across the world

are graphic, it will mostly be imagined

graphics, and one thing I’ve noticed over the years is that, even in hell,

certain lines never get crossed when it comes to torture. I give you this

general warning now, but at the same time, I don’t want the warning itself to

catalyze any anxieties about course content. No one to date has told me they

had any such problems with the material, but if you do have problems, that’s

okay. We’ll manage them.

Conversely,

I don’t want us to be dismissively cavalier or angrily bombastic in conference

about the people who originally make those damning judgments of others. We are

respectful and dispassionate religiologists, usually

looking at these idea systems from the outside and lacking the conditioned

understanding that these believers themselves possess. And I say “usually”

because please don’t forget that some of your own conference colleagues may

themselves believe in hell and in some of the reasons for going there (although

I will of course never ask anyone about personal beliefs). If nothing else, our

cavalier dismissiveness when we’re tempted to derisively roll our eyes at those

believers might in itself be unscholarly because it dead-ends our own attempt

to understand the reasons and habituations that go into the formation of

beliefs held by others. (I think Ratliff’s documentary on Hell House is a great

example of dispassionate, respectful reportage.) In the end, I would simply ask

that we never be inconsiderate and cavalier, either when addressing delicate

personal issues or when studying other people who do not believe the way we do.

IV.

Incompletes, absences and extensions – the draconian stuff so PLEASE READ

As the great

Warring States legalist Han Feizi warned, indulgent

parents have rowdy kids and overly lenient rulers have inefficient subjects; by

extension, a permissive teacher can’t maximize a student’s learning potential.

By laying down the law now, we’ll also never need to raise it again in the

future, and I can pretend to be a kindly Confucian rather than a draconian

legalist.

“An Incomplete [IN] is permitted in a course where the level

of work done up to the point of the [IN] is passing, but not all the work of a

course has been completed by the time of grade submission, for reasons of

health or extreme emergency, and for no other reason,” according to the Reed

College Faculty Code (V A). “The decision whether or not to grant an IN in a

course is within the purview of the faculty for that course.” Like many of my colleagues, I read this as

restricting incompletes to acute, extreme emergencies and health crises that

have a clear beginning date and a relatively short duration only, that are

outside the control of the student, and that interrupt the work of a student

who was previously making good progress in a course. Incompletes cannot be

granted to students unable to complete coursework on time due to chronic

medical conditions or other kinds of ongoing situations in their academic or

non-academic life. Accommodation requests need to be timely and go through

established channels.

Regular, prepared, and disciplined conferencing is intrinsic

to this course, and so at a certain point when too many conferences have been

missed – specifically six which translates into a “fail” for the course – it

would logically be advisable to drop or withdraw and to try again another

semester. There’s no shame in that. Longer-term emergencies indeed happen, and

you ought to make use of Student Services when they do. (If you have

accommodations via DSS, please 1.) come talk to me about them so we’re on the

same page as to what they mean, and 2.) if I’m failing to meet them, please

contact me [or DSS] within one week so we can fix it.) In sum, I’ll help you

out as much as I can to get you across the finish line, but it’s the same

finish line for everyone and to be fair to your colleagues I need to have you

there in the race. To that end, I would ask that you please e-mail me whenever

you are absent just to let me know you’re okay. (More and more students seem to

be doing this without prompting anyway, perhaps because we’ve all become

increasingly dependent upon virtual connectivity.)

I’m happy to give paper extensions for medical problems and

emergencies, and you should take advantage of the Health and Counseling Center

in such circumstances. Please note that here, too, the honor principle provides

a standard for expectations and behavior, meaning that none of us (including

myself) should resort to medical reasons when other things are actually impeding our work. (Please just be honest. It’s as

simple as that.) In non-medical situations, late papers will still be

considered, but the lateness will be taken into account

and no comments given. Ken’s Subjectivity Curve: The later it is, the more

subjective Ken becomes. It's a gamble. I’m not a legalist like Han Feizi, but even the Confucians resorted to hard law when

ritualized conduct and exemplary leadership failed.

|

|

Karmic retribution for missing a conference |

V. Schedule

|

27 Aug |

Introduction: “The worst of all possible worlds....” |

|

|

29 Aug |

The first flickers of flame |

·

Alan

Bernstein, “Thinking about hell,” The

Wilson quarterly 10.3 (1986): 78-89. (JSTOR.) ·

“Questions

and answers about death and afterlife,” in How different religions view death and afterlife 2nd

ed, Christopher Jay Johnson and Marsha G. McGee, eds. (Philadelphia, PA: The

Charles Press, 1998), 266-300. (Moodle.) |

|

31 Aug |

Mary, Mary quite contrary |

·

“The

[Greek] apocalypse of the Holy Mother of God concerning the chastisements” (9th-10th

cen). (Handout.) ·

Mary

K. Baxter, A divine revelation of hell

(New Kensington, PA: Whitaker House, 1993), 15-50. (Moodle and handout.) |

|

|

||

|

3 Sep |

Labor Day |

|

|

|

“Old school” comparison before the postmodernist sea

change |

·

James

George Frazer, “The transmigration of human souls into animals,” in The Golden Bough (Part V, Vol II): Spirits

of the corn and of the wild (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1935),

285-309. (Moodle.) ·

J.J.L. Duyvendak,

“A Chinese ‘Divina Commedia’,” T’oung Pao 41

(1952): 255-316, 414. (JSTOR.) |

|

5 Sep |

General theories on comparison: The problem of what we’re

looking at in space and time |

·

Clifford

Geertz, “Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture,” The interpretations of cultures

(Hammersmith, U.K.: Fortana Press / HarperCollins:

1973), 3-30. ·

Carol

Zaleski, “Evaluating near-death testimony,” Otherworld journeys: Accounts of near-death experience in medieval

and modern times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 184-205. |

|

7 Sep |

General theories on comparison: The problem of who is

doing the looking |

·

Thomas

A. Tweed, Crossing and dwelling: A

Theory of religion (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 1-53,

143-150, 187-207, 241-243. (Moodle.) |

|

|

||

|

10 Sep (cnt on next page) ↓ |

General theories on comparison: A validated and valuable

tool? Exploratory 1 |

·

Wendy

Doniger, “Post-modern and –colonial –structural

comparisons,” in A magic still dwells:

Comparative religion in the postmodern age, Kimberley C. Patton and

Benjamin C. Ray, eds. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000),

63-74. (Moodle.) ·

Barbara

Holdrege, “What’s beyond the post? Comparative analysis as critical method,”

in A magic still dwells: Comparative

religion in the postmodern age, Kimberley C. Patton and Benjamin C. Ray,

eds. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000), 77-91. (Moodle.) ·

Winnifred

Fallers Sullivan, “American religion is naturally comparative,” in A magic still dwells: Comparative religion

in the postmodern age, Kimberley C. Patton and Benjamin C. Ray, eds.

(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000), 117-130. (Moodle.) ·

Kimberley

C. Patton, “Juggling torches: Why we still need comparative religion,” in A magic still dwells: Comparative religion

in the postmodern age, Kimberley C. Patton and Benjamin C. Ray, eds.

(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000), 153-171. (Moodle.) ·

William

E. Paden, “Elements of a new comparativism,” in A magic still dwells: Comparative religion

in the postmodern age, Kimberley C. Patton and Benjamin C. Ray, eds.

(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000), 182-192. ·

Jonathan

Z. Smith, “The ‘end’ of comparison: Redescription and rectification,” in A magic still dwells: Comparative religion

in the postmodern age, Kimberley C. Patton and Benjamin C. Ray, eds.

(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000), 237-241. (Moodle.) |

|

12 Sep |

Historical aside I: Satan |

·

Miguel

A. De La Torre and Albert Hernandez, “The birth of Satan: A textual history,”

The quest for the historical Satan

(Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2011), 49-95. (Moodle.) |

|

14 Sep |

Historical aside II: Purgatory |

·

Jacques

Le Goff, “The logic of purgatory” and “Social victory: Purgatory and the cure

of souls,” The birth of purgatory,

Arthur Goldhammer, trans. (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1986), 209-234, 289-333. (Moodle.) |

|

|

||

|

17 Sep |

Proposals presented |

Our maps for the descent: Your proposal for the study of a

particular “pedagogical pilgrimage of retributive hell.” |

|

19 Sep |

Our baseline: The Lucan hell I |

·

Ehrman, Bart D. Heaven

and hell: A history of the afterlife (New York: Simon and Schuster,

2020), 81-146. (Moodle.) ·

Eileen

Gardiner, ed. Visions of heaven and

hell before Dante (New York: Italica Press,

1989), 1-63. (Text.) |

|

21 Sep |

Sources and patterns in the earliest hells? Written paper proposals due |

·

Carol

Zaleski, “The other world: medieval itineraries,” “Obstacles” and “Reentry,” Otherworld journeys: Accounts of

near-death experience in medieval and modern times (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1987), 45-94. (Moodle.) |

|

|

||

|

24 Sep |

The Lucan hell II |

·

Eileen

Gardiner, ed. Visions of heaven and

hell before Dante (New York: Italica Press,

1989), 65-133. (Text.) |

|

26 Sep (cnt on next page) ↓ |

The Lucan hell III (focusing on St. Patrick’s purgatory) Exploratory 2 |

·

Eileen

Gardiner, ed. Visions of heaven and

hell before Dante (New York: Italica Press,

1989), 135-148. (Text.) ·

Jacques

Le Goff, “Discovery in Ireland: ‘St. Patrick’s purgatory’,” The birth of purgatory, Arthur Goldhammer, trans. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1986), 193-201. (Moodle.) ·

Carol

Zaleski, “The otherworld journey as pilgrimage: St. Patrick’s purgatory,” Otherworld journeys: Accounts of

near-death experience in medieval and modern times (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1987), 34-42. (Moodle.) ·

Pedro

Calderon de la Barca, “Act the Third; Scene X,” The purgatory of St. Patrick (Teddington,

U.K.: The Echo Library, 2007), 96-104. (Moodle.) |

|

28 Sep |

The Lucan hell IV |

·

Eileen

Gardiner, ed. Visions of heaven and

hell before Dante (New York: Italica Press,

1989), 149-236. (Text.) |

|

|

||

|

1 Oct |

Modern theological disagreements about the Lucan hell I |

·

Zachary

J. Hayes, et al, Four views on hell

(Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996), 11-88. (Text.) |

3 Oct |

Modern theological disagreements about the Lucan hell II |

·

Zachary

J. Hayes, et al, Four views on hell

(Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996), 91-178. (Text.) |

|

|

5 Oct |

Modern evangelical Christians who have visited the Lucan

hell Exploratory 3 |

·

Howard

Storm, My descent into death: A second

chance at life (New York: Doubleday, 2005), 1-29. (Moodle.) ·

Bill

Wiese, 23 minutes in hell (Lake

Mary, FL: Charisma House, 2006), 1-53. (Moodle.) ·

Yong-Doo

Kim, Baptize by blazing fire: Divine

Expose of heaven and hell (Lake Mary, FL: Creation House, 2009), TBD.

(Handout.) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

8 Oct |

Hell house I |

·

Hell

House (Primary sources to be provided) ·

George

Ratliff, Hell house (documentary)

(at Ken’s house, exact timing TBA) |

|

|

10 Oct |

Hell house II |

·

Hell

House (Primary sources to be provided) |

|

12 Oct |

Hell house III Exploratory 4 |

·

Hell

House (Primary sources to be provided) ·

Brian

Jackson, “Jonathan Edwards goes to Hell (House): Fear appeals in American

evangelism,” Rhetoric review 26.1

(2007): 42-59. (JSTOR.) ·

Ann

Pellegrini, “‘Signaling through the flames’: Hell

House performance and structures of religious feeling,” American quarterly 59.3 (2007): 911-935. (JSTOR.) |

|

|

FALL BREAK |

|||

|

22 Oct |

Specific theories for hell I: Symbol |

·

Geertz,

Clifford, “Ethos, world view, and the analysis of sacred symbols,” The interpretations of cultures

(Hammersmith, U.K.: Fortana Press / HarperCollins:

1973), 126-141. ·

Ricoeur, Paul. “‘The Hermeneutics of symbols and philosophical

reflection: I,” The conflict of

interpretations (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1974),

287-314. ·

Frankenberry,

Nancy. “A ‘mobile army of metaphors’,” in Radical interpretation in

religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 171-187. |

|

|

24 Oct |

Specific theories for hell II: Narrative |

·

Stanley

Hauerwas, “The self as story: A reconsideration of the relation of religion

and morality from the agent’s perspective,” in Vision and virtue: Essays in Christian ethical reflection (Notre

Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981), 68-89. ·

Alasdair

MacIntyre, “The virtues, the unity of a human life

and the concept of a tradition,” in After

virtue (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), 204-225. ·

Ricoeur, Paul. “Life: A story in search of a narrator,” A Ricoeur

reader: Reflections and imagination, Mario J. Valdés, ed. (Toronto:

University of Toronto Press, 1991), 425-437. |

|

26 Oct |

Specific theories for hell III: Projection |

·

Guthrie,

Stewart Elliott, Faces in the clouds: A

new theory of religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 62-90. ·

Boyer,

Pascal, Religion explained: The

evolutionary origins of religious thought (New York: Basic Books, 2001),

137-167. |

|

29 Oct |

Specific theories for hell IV: Surveillance |

·

Norenzayan, Big gods: How

religion transformed cooperation and conflict (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 2013), 13-54. ·

Brook,

Timothy, Jerome Bourgan and Gregory Blue,

“Tormenting the dead,” in Death by a

thousand cuts (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 122-151. |

|

31 Oct |

A communal pilgrimage through an “other” hell I |

TBA |

|

2 Nov |

A communal pilgrimage through an “other” hell II |

TBA |

|

|

||

|

5 Nov |

Packing our bags for the trip I |

[Meet with Ken individually to prepare for your

presentations.] |

|

7 Nov |

Packing our bags for the trip II Description paper due |

[Meet with Ken individually to prepare for your

presentations.] |

|

9 Nov |

Our first guided tour of hell |

Guide: _______________________ |

|

|

||

|

12 Nov |

Our second guided tour of hell |

Guide: _______________________ |

|

14 Nov |

Our third guided tour of hell |

Guide: _______________________ |

|

16 Nov |

Our fourth guided tour of hell |

Guide: _______________________ |

|

|

||

|

19 Nov |

Our fifth guided tour of hell |

Guide: _______________________ |

|

21 Nov |

Our sixth guided tour of hell |

Guide: _______________________ |

|

23 Nov |

Thanksgiving |

|

|

|

||

|

26 Nov |

Literary journeys old: Dante I |

·

Dante

Alighieri, The divine comedy: Inferno,

Allen Mandelbaum, trans. (New York: Bantam, 1992), cantos I-XI. |

|

28 Nov |

Literary journeys old: Dante II |

·

Dante

Alighieri, The divine comedy: Inferno,

Allen Mandelbaum, trans. (New York: Bantam, 1992), cantos XII-XXII. |

|

30 Nov |

Literary journeys old: Dante III Exploratory 5 |

·

Dante

Alighieri, The divine comedy: Inferno,

Allen Mandelbaum, trans. (New York: Bantam, 1992), cantos XXII-XXXIV. |

|

|

||

|

3 Dec |

Literary journeys new: C.S. Lewis |

·

C.S.

Lewis, The great divorce. (Online.) |

|

5 Dec |

Coda: Dousing the flames |

|

|

|

||

|

12 Dec (noon) |

Comparison paper due (with SASE if you want comments).

Please note that I won’t accept any

late work after 5 p.m. on the last day of final examinations. |

|

|

From my trip to an amusement

park at the English seaside

recently. Why is hell ... amusing? |

|

VI. Consciousness of conference

technique

Much of our educational system seems designed to discourage

any attempt at finding things out for oneself, but makes learning things others

have found out, or think they have, the major goal. –

Anne Roe, 1953.

At times it is useful to step back and

discuss conference dynamics, to lay bare the bones of conference communication.

Why? Because some Reed conferences succeed; others do not. After each

conference, I ask myself how it went and why it progressed in that fashion. If

just one conference goes badly or only so-so, a small storm cloud forms over my

head for the rest of the day. Many students with whom I have discussed

conference strategies tell me that most Reed conferences don't achieve that

sensation of educational nirvana, that usually students do not leave the room

punching the air in intellectual excitement. I agree. A conference is a much

riskier educational tool than a lecture, and this tool requires a sharpness of

materials, of the conferees and of the conference leader. It can fail if there

is a dullness in any of the three. Yet whereas lectures merely impart

information (with a "sage on the stage"), conferences train us how to

think about and interact with that information (with a "guide on the

side"). So when it does work....

The content of what you say in

conference obviously counts most of all, so how do you determine in advance

whether you’ve got something worthwhile to say? The answer is simple if you

don’t just quickly read the assigned materials and leave it unanalyzed. So how

do you analyze it? A colleague and friend at Harvard, Michael Puett, writes, “the goal of the analyst should be to

reconstruct the debate within which such claims were made and to explicate why

the claims were made and what their implications were at the time." A religious or philosophical idea doesn’t get

written down if everyone already buys it; it’s written down because it’s news.

As new, we can speculate on what was old, on what stimulated this reaction.

Think of these texts as arguments and not descriptions, and as arguments, your

job is to play the detective, looking for contextual clues and speculating on

implications. I will give you plenty of historical background, and if you look

at these texts as arguments, you will get a truer picture.

In addition to content, there are

certain conference dynamics that can serve as a catalyst to fully developed

content. I look for the following five features when evaluating a conference:

1.

Divide the allotted time by the

number of conference participants. That resulting time should equal the

leader's ideal speaking limits. (I talk too much in conference. Yet when I say

this to some students, they sometimes tell me that instructors should feel free

to talk more because the students are here to acquire that expertise in the

field. So the amount one speaks is a judgment call,

but regardless, verbal monopolies never work.)

2.

Watch the non-verbal dynamism. Are

the students leaning forward, engaging in eye contact and gesturing to drive

home a point such that understanding

is in fact taking on a physical dimension? Or are they silently sitting back in

their chairs staring at anything other than another human being? As a

conference leader or participant, it's a physical message you should always

keep in mind. Leaning forward and engaging eye contact is not mere appearance;

it indeed helps to keep one focused if tired.

3.

Determine whether the discourse is

being directed through one person (usually the conference leader) or is

non-point specific. If you diagram the flow of discussion and it looks like a

wagon wheel with the conference leader in the middle, the conference has, in my

opinion, failed. If you diagram the flow and it looks like a jumbled,

all-inclusive net, the conference is more likely to have succeeded.

4.

Determine whether a new idea has been

achieved. By the end of the conference, was an idea created that was new to

everyone, including the conference leader? Did several people contribute a Lego

to build a new thought that the conferees would not have been able to construct

on their own? This evaluation is trickier because sometimes a conference may

not have gone well on first glance but a new idea evolved

nonetheless. The leader must be sure to highlight that evolution at conference

end.

5.

Watch for simple politeness.

"Politeness" means giving each other an opportunity to speak,

rescuing a colleague hanging out on a limb, asking useful questions as well as

complimenting a new idea, a well-said phrase, a funny joke.

If you ever feel a conference only

went so-so, then instead of simply moving on to the next one, I would urge you,

too, to evaluate the conference using your own criteria and figuring out how

you (and I) can make the next one a more meaningful experience. Preparation is

not just reading the assigned pages; it’s reading and then thinking through

something in that reading, developing a thought and getting it ready to

communicate to someone else.

In

the end, as long as you are prepared and feel

passionate about your work, you should do well, and if passion ever fails, grim

determination counts for something.

VII. The exploratory

Sometimes conferences sing. Yet just

when I would like them to sing glorious opera, they might merely hum a bit of country-western. After my first year of teaching at Reed, I

reflected upon my conference performance and toyed with various ideas as to how

to induce more of the ecstatic arias and lively crescendos, and I came up with

something I call an "exploratory."

Simply

put, an exploratory is a one-page, single-spaced piece in which you highlight

one thought-provoking issue that caught your attention in the materials we are

considering. This brief analysis must show thorough reading and must show your own thoughtful extension –

·

Your own informed, constructive criticism of the author

(and not just a bash-and-trash rant);

·

Your own developed, thoughtful

question (perhaps even inspired by readings from other classes) that raises

interesting issues when seen in the light of the author's text;

·

Your own application of theory and

method to the primary source;

·

Your own personal conjecture as to

how this data can be made useful; or (best of all)

·

Your own autonomous problem that you

devised using the same data under discussion.

I am not here looking for polished

prose or copious (or any) footnotes – save all that for our formal papers. (I

do not return exploratories with comments unless a

special request is made.) Exploratories are not full, open-heart surgeries performed

on the text. Instead, exploratories tend to be

somewhat informal but focused probes on one particular aspect

in which you yourself can interact with the text and can enter into the

conversation.

What

is not an exploratory? It is not

merely a topic supported by evidence from the book, nor is it a descriptive

piece on someone else's ideas, nor is it a general book report in which you can

wander to and fro without direction. Bringing in

outside materials is allowed, but the exploratory is not a forum for ideas

outside that day's expressed focus. (Such pieces cannot be used in our

conference discussions.) Also, don’t

give into the temptation of just reading the first few pages of a text and then

writing your exploratory. (What would you

conclude if you received a lot of exploratories that

all coincidentally tackled an issue in the first five pages of the

reading?) It is instead a problematique, an issue with attitude.

The

best advice that I can give here is simply to encourage you to consider why I am requesting these exploratories from you: I want to see what ignites your

interest in the text so I can set the

conference agenda. That is why they are due the evening before a conference. Thus

late exploratories are of no use. (Being handed a

late exploratory is like being handed your salad after you've eaten dessert and

are already leaving the restaurant.) I

will use them to draw you in, parry your perspective against that of another,

and build up the discussion based on your views. Exploratories

help me turn the conference to issues that directly interest you. They often

lead us off on important tangents, and they often return us to the core of the

problem under discussion. So if you are struggling

with finding "something to say," simply recall why I ask for these exploratories in the first place. Is there something in the

text you think worthy of conference time? Do you have an idea you want to take

this opportunity to explore? Here is your chance to draw our attention to it.

Your perspectives are important, and if you have them crystallized on paper in

advance, they will be easier to articulate in conference.

Since

I began using exploratories, most students have

responded very favorably. Students like the fact that it is a different form of

writing, a bit more informal and more frequent, somewhat akin to thinking

aloud. It forces one not just to read a text but to be looking for something in

that text, to engage that text actively. And it increases the likelihood that

everyone will leave the conference singing Puccini.

The

boiling caldrons of hell

from

a 12th century Song dynasty cliff face (Dazu nr Chengdu)