|

Rel. 313: Early and medieval

Chinese Buddhism “The

land of gems meets the land of bronze” Syllabus

(Spring 2021) |

K.E. Brashier Office hours: T 12 noon-1.30

p.m.; Th 1-2.30 p.m. |

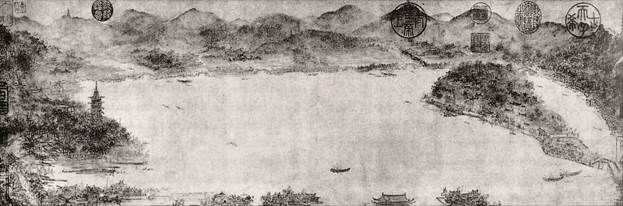

Built

in 975 CE on the eastern edge of the consolidating Song empire, the Leifeng pagoda 雷峰塔 survived for almost a thousand years. It was immortalized in

painting and poetry on the banks of Hangzhou’s famous West Lake, but perhaps

its own longevity owes to the fact that it was literally built of protective

sutras. As one surviving inscription explains, “On the day the pagoda was

completed, the Avatamsaka and various sutras

were engraved on the walls circumscribing the eight sides of the pagoda,” and

indeed some of those inscriptions from the pagoda’s lower walls have survived.

The Leifeng Pagoda in a Song dynasty handscroll by Li Song

(active 1190-1230)

Yet

when it finally collapsed in 1924, archeologists soon realized that this

textual protection indeed extended from head to toe because the bricks of its

seventh and uppermost story had holes in them with copies of a scripture, the Treasure-chest

seal dhāranī sutra, rolled up inside each.

|

|

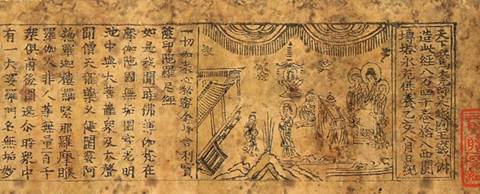

The Baojieyin tuluoni jing寶篋印陀羅尼經 or Treasure-chest

seal dhāranī sutra (one sample of which is the oldest printed work in the

Library of Congress) |

|

|

These woodblock-printed sutras were rolled up inside the bricks that comprised the pagoda’s uppermost level. The pagoda a

year or two before it

collapsed in 1924. |

|

|

Ironically, this sutra’s frame story is about

scriptures inside the ruins of a Buddhist structure. In what was once a very

popular scripture, the Buddha himself came across a garden with a dilapidated

stupa in the middle of it, and emotionally moved by it, he explained to his

disciples that the sutra therein had become the “complete body relics” 全身舍利 of a buddha and that whenever

this sutra was stored inside a stupa or statue, it is the Buddha, worthy

of veneration. Buddhist texts aren’t just texts.

The very fact that a text might

capture the essence of the Buddha is ironic in itself.

Buddhism begins with the idea of emptiness, of all things being “empty” of

persisting, independent qualities. We’ll talk a lot

about emptiness in this course, which is paradoxical because emptiness is empty

of borders and immune to being boxed up in dualistic words, whether they be in

sutras or in a teacher’s pathetic attempts to explain them. So

a worded sutra actually transforming into the “complete body relics” of a

buddha is interesting in itself. Yet in a very real sense, the whole of Buddhism

is about different ways of expressing inexpressible emptiness, those attempted

means of expression being 1.) through the Buddha himself who is an exemplar to

mimic, 2.) through those sutras that try to give words to the wordless, 3.) or

through the ritual practices of the community that would have us do Buddhism

rather than define it. The Buddha, the sutras (or “dharma”) and the community (or

“sangha”) constitute the “three jewels” of Buddhism. They’re

three different kinds of trajectory toward the ineffable. Our own course will

focus on the second jewel, the sutras, although we’ll

also read a famous biography of the Buddha as well as sample the vinaya code that ritually orchestrates the Buddhist

community.

I.

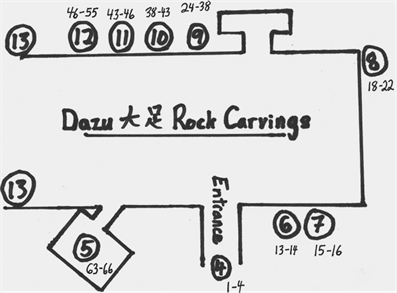

Dazu: our guiding metaphor

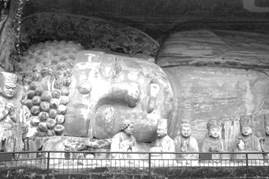

Also in the Song dynasty and on the

same latitude as Hangzhou but now on the western side of the empire, a little-known

monk named Zhao Zhifeng 趙智風 (b.

1159) likewise endeavored to inject sutra texts into a building project, but

instead of rising above the landscape, he was digging into it. His artisans and

sculptors carved out a

long horseshoe-shaped cliff stretching hundreds of meters, covering it with thousands

of Buddhist statues and adding inscriptions totaling more than a hundred

thousand characters, all preserving a physical survey of Chinese Buddhism. The impressive cliff face of Dazu 大足has

survived centuries of weather and cultural revolutions, and it’s

now a World Heritage Site, attracting tourists from across the planet.[1] When

visitors arrive at the site, they immediately discover there’s no single vantage

point to shoot that one great vacation photo essentializing the whole of it. No

Mt. Rushmore moment.[2] Because

of the terrain’s shape, they instead find themselves immediately inside the

horseshoe, walking along the base of these three- to four-story cliffs. The

three giants of the Avatamsaka sutra –

here literally giants – stand next to a thousand-armed Guanyin (a.k.a. Avalokiteśvara)

from Tiantai Buddhism’s Lotus sutra. Images and texts straight out of the Pure Land sutras

frame an entrance to a cave dedicated to the ten bodhisattvas of the Chinese

apocryphal Perfect enlightenment sutra.

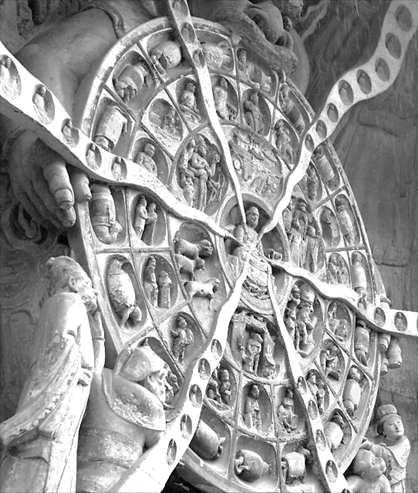

The Buddha’s life story stretches across the east end or “bottom” of the

horseshoe with a particularly stunning gargantuan portrayal of his entering

into Nirvana, flanked by an impressive wheel of transmigration to the south and

a gory panorama of hell’s tortures to the north.

There’s of

course a metaphor coming on: just as we can’t shoot a picture that

essentializes all of Dazu, Buddhism in general and text-based Chinese Buddhism

in particular offer no panopticon to tidily view the whole of it. There’s no single dogma, no papal authority, no Nicene or

Apostles Creed recited every Sunday in churches of diverse denominations around

the world. When it comes to the texts themselves, there’s

no Bible but instead thousands of different sutras, some more popular

than others depending on time, place and community. There’s also no either/or exclusivity of Abrahamic traditions

categorically damning outsiders and hence clearly defining itself, and when it

comes to subdivisions within, there’s no notion of “I am a Lutheran, not a

Catholic” or “I am a Missouri Synod Lutheran, not a Wisconsin Synod Lutheran.”

While we might divvy up Chinese Buddhism in terms of discourses or – using that

nebulous term – “traditions” by associating certain people with certain sutras,

that can be highly misleading. The great Tang scholar-monk Zongmi

was a patriarch of both the Huayan and Chan

(a.k.a. Zen) traditions, Chan monasteries regularly featured Guanyin statues

even though Guanyin would technically be of the Tiantai

(Lotus sutra) tradition, and the

laity rarely grouped themselves into discrete communities like sports

franchises competing against one another to win the world cup. More and more, scholars

now speak, not of Buddhism, but Buddhisms. That sense of an amorphous idea system is like

being down inside Dazu where sutra

images and inscriptions all blend into one another and where there’s

no kiosk selling that unique iconic postcard essentializing the whole place

with a singular, all-inclusive image and a simple “Wish you were here” message

on back.

|

The Avatamsaka giants

– a small segment of the Dazu horseshoe cliff. To grasp its size, notice the

people with their umbrellas in the lower right corner. |

|

|

The

first of the ten hell kings at Dazu Zhao Zhifeng

himself – notice how he’s

surrounded by texts. |

|

Yet that doesn’t mean there’s no distinctive “flavor” to the Buddhism

preserved in Chinese texts (as I now awkwardly mix my metaphors), just as

there’s something about Chinese food that sets it apart from, for example,

Indian. (By the way, flavors are likewise notoriously difficult to reduce into

words.) As we explore the Chinese sutras that would propagate Buddhism,

we need to ask a particular set of questions regarding these texts. What is it

about the Mahayana sutras that made them fitter for travel and more appealing

to Chinese rulers and educated laity? Is it reasonable to highlight filial

piety – a favorite Confucian notion – in Dazu’s narration of the Buddha’s own

life? Did Chinese Daoism influence the selection of Indian texts to morph into

Chan Buddhism? Why did some ideas take China by storm such as hell and reincarnation

whereas others generated endless friction such as the renunciant lifestyle that

left the family behind? In sum, how does

the textual corpus of a complex religion negotiate this kind of established

environment that already boasts text-rich

Confucianism, Daoism and other-isms?

Our focus on sutras that were popular in China requires a

different kind of syllabus, and as we are a small-ish

group, I suggest we indulge ourselves in a bit of experimentation. Instead of

giving you the standard, calendrically-based course outline – “On Day N we will

read Text X” – I am resorting to a spatial allegory. To hold this course

together, we will use Dazu’s own physical layout because it conveniently depicts

all the sutra traditions one normally finds in Chinese Buddhism surveys (e.g. the big four of Huayan, Tiantai, Pure Land and Chan) and it graphically depicts

more popular expressions of Buddhism found among the laity (e.g. the hell

imagery or filial piety stories). For us, Dazu can serve as a solid microcosm

in time and space. On one hand, we could simply claim our course is painting

the immediate landscape of ideas that informs this one place in Western China

eight hundred years ago; on the other hand, we could extrapolate Chinese Buddhisms from this spot to understand the grander

arguments being made about the Buddhist cosmos. And to be honest, it’s simply

rather comforting to have a small, physical, fully-contextualized

nugget at the heart of the immense complexity of amorphous Indian and Chinese Buddhisms.

II. Objectives and outcomes

Cleary

defined objectives and testable outcomes … these new syllabi requirements are

rather ironic for a course about triangulating ineffable emptiness. Yet like

words, accreditation requirements perhaps “also bear the marks of

emancipation.” (You’ll get what that means when we

read the Chan sutras.)

Course objectives

A.

You

will become familiar with Chinese sutra-based Buddhism by directly

reading its historically famous scriptures. Note what this objective isn’t: This course isn’t a survey of Buddhism or of

Chinese Buddhism; it isn’t about Buddhists and their experiences; it isn’t

about Buddhism as an institution framed by economics, politics or sociological

concerns; it isn’t about modern practice. This course is focused on how the

sutras attempt to explain the Buddhist Weltansicht,

the Buddhist vision of reality. Prior to China’s “sphere-ization” a la Western rubrics – that is, prior to China

adopting Western umbrella concepts such as “economics,” “politics” and

“sociology” in the early 20th century – the concepts of “philosophy” and “religion” weren’t recognized genres or separate from one another. In

this course, we’re using these sutras to study

Buddhist “philosophy” in the sense that it’s about the nature of reality

itself, and that then morphs into “religion” because it dictates a particular

way to act and a particular path to salvation.

B.

You

will learn to closely and carefully read sutras, a writing style no doubt very unfamiliar

to you.[3]

There are numerous reading conventions to understand lest the sutras seem

boring, and you will learn to appreciate how these texts aren’t just bequeathing

information but are actually performative in nature. For example,

sutras often begin with long name lists of humans and gods attending that particular sermon of the Buddha – sometimes hundreds of

names – and while that might seem rather dull, reading these lists is actually

getting you to experience the aggregate nature of reality (in my

opinion), making you feel the ontological premise of unit after unit

after unit that informs “emptiness.” Both for us modern readers and for the

original reciters, these texts do something. For the latter, they even

become the Buddha himself according to the Treasure-chest seal dhāranī sutra, and to appreciate that, we

need to learn how to read, how to do the sutra.

C.

Given

the nature of emptiness – or the lack of nature of emptiness – you will learn

how to respectfully and objectively analyze this analysis-defying

content. This is a regular problem in religious theory that gets

exponentially magnified in Buddhism. How do you talk about religious

experience? How do you picture G-d? A couple weeks ago on the Facebook

“Sinology” page, a new teacher expressed his exasperation at teaching Buddhism

because his students’ essays largely resorted to “personal opinions arguing for

the virtues or correctness of Buddhism, Zen, meditation, etc.” Relying on our prior

assumptions and judgments potentially leads to vague endorsements of spirituality

or to dismissive condemnations of the benighted other. “What methods,

resources, or tips can anyone suggest for getting undergrads to write about

Buddhism (or religion in general) from an academic/scholarly/objective

perspective?” he asked. I answered, “I start out my own course on

Chinese Buddhism with a discussion of basic emptiness and then spend the

semester with historical works that try to triangulate around that emptiness as

thinkers and practitioners paradoxically struggle to give it a kind of

definition (via analogy, analysis, abhidharma-style

deconstruction, Daoist-style apophatic logic, art, etc.). My students' papers

need to be a continuation of that struggle, meaning they can't

resort to the vagaries of what's sometimes called ‘peek-a-boo’ or ‘protective’

language in religious studies. In other words, I make the problem you're

describing the very theme of the course and challenge them to continue the

struggle (even if we're not Buddhists or Buddhologists).”

Emptiness is the ultimate in peek-a-boo terms, and we’ll

learn the rules of that game in this course.

Learning outcomes

All

that boils down into the following:

A.

Content: Students will be able to

conduct a formal and contextual analysis of a complex philosophical system that

in turn leads to a particular religious manifestation.

B.

Medium: Students will learn how to

master close reading of an unfamiliar textual genre via carefully engaging the

primary texts.

C.

Output: Finally, students will

demonstrate their own ability to triangulate around and articulate complex

ideas that, on the surface, would defy any attempt at that articulation.

III. But how do we achieve those objectives and

outcomes … online?

On 6 June 2020, Peter Sagal on NPR’s news quiz “Wait, wait … don’t tell me” described how education will look this year because of the pandemic pause:

So school administrators are already thinking about rules for the fall. The LA school district has said that kids won't be eating lunch together in the cafeteria but alone in their seats in the classroom. Congratulations, nerds. You're not the only ones now eating with the teacher…. Every student at recess will be given their own ball and – think of the great games…. you can play when everyone has a ball. Like, everyone stares sadly at their ball…. Can you imagine the humiliation for the kids like me who are going to be picked last for holding their own ball?[4]

Even if you’re living on campus, it may feel like we’ll each be holding our own ball this semester, and I myself am not very coordinated when it comes to any sports, even just holding things. As for Zoom’s digital medium, my PhD thesis was on Chinese tombstone epigraphy from two thousand years ago, about as far away as you can get from Wi-Fi and ethernet. So I’m not an internet-first person (much to the chagrin of my husband who’s an Intel software engineer); I’ve long argued against screen-based learning because less is retained; and I idealize Reed’s conference system of education through direct contact because I like creating conditions in which students productively think on the spot. But I’m simply not as young as I once was – I’m retiring at the end of this semester – and Reed needs to thin out its in-person campus space to reduce risk. So … here’s your bouncing ball.

Last semester’s online teaching made me feel like walking into an appliance store and facing a wall of separate televisions, the presenters all facing forward and not interacting with one another. Even in a large in-person conference, I could have at least turned toward the speaker and interacted in gesture and facial expression. Individual contact could still be made. Now no one knows when my attention is fully turned on them and I’m looking them straight in the eyes. It’s a bit lonely and unsatisfying, and I suspect that, for you as well, a typical class often ranked closer to watching TV rather than to actually engaging other humans. There were even several embarrassing cases when, although I thought someone was engaged because they were looking at me through their Zoom window, I came to awkwardly realize they weren’t really “with” me at all.

There’s a learning curve, and we must adapt. For example, last semester I’d crafted nice PowerPoint-supported “starter” arguments, but despite the best of intentions – great arguments, nice graphics and pretty pictures – I managed to kill interactivity in the process because I was indeed starting class by making it feel more like a TV show than a meeting. This semester I’ll try to keep those PowerPoints to a minimum, but let me know if it ever gets too minimal. (I have a lot I want to tell you about how Buddhist thought works in a Chinese context.)

The student survey many of you filled out last summer gave me lots of useful insights about online teaching. You generally like synchronous learning on a regular schedule. You want smaller groups and shorter sessions for Zoom discussions. You don’t want group projects. If there are to be professorial video presentations, you like them recorded but not necessarily in long (i.e. boring) segments nor as voice-over PowerPoint presentations without seeing the teacher. You like handouts and outlines to go with the audio recordings. You want flexibility should the need arise. I’ll try to do all of that, although please be gentle with me because, not only is this online medium awkward for me, but also I’m additionally teaching an online intro this semester with almost fifty students in it.

“I’ll try to do all of that” … within reason. One thing I’m loathe to do is lower my standards, even if I’m willing to expand them a bit. That is, if you work hard, keep up with the readings and develop a sincere appreciation for learning this material, then you’ll get the full experience out of this material as you would in any normal year. Or at least I’ll try to make it so. I might “expand” my standards a bit by subjectively lowering the fail threshold a little if I see you legitimately struggling with the current situation, paying the very real costs of pandemic pressures. But before I lower that threshold, we’ll resort to making accommodations. For example, if it’s simply impossible to fully engage online for various reasons, we’ll find other ways for you to engage, such as through more writing assignments or even exams to ensure you’re up-to-speed and thinking about the material.[5] That is, I’ll be especially accommodating this year to get you to the finish line, but I still want everyone to cross the same finish line.

So …

some things I’ve been working on in this transition to online

teaching:

·

As noted, there will sometimes be videos (Covid-eos?)

and audios – some long, some short – added to the Moodle listings for any particular day, the latter usually accompanied by a handout.

Please listen/view them before the relevant conference. For example, I have

more than a dozen seven-minute pieces explaining Buddhist basics for you – I

call them my “piton presentations” because they’re little assists in scaling

the Buddhist cliff face – but I’m not sure if I should present them in

conference (thereby giving you a chance to ask questions) or record them as

audio shorts (both freeing up conference time and more conveniently accessible

for reference). I’ll ask you to choose.

·

Although my computers only crashed once during a

conference last semester (and then only for two or three minutes), I’m still clunky when it comes to Zoom. For example, did you

know the Zoom interface for the presenter is different from that of the

participants? If I show you a piece of text via sharing my screen – something

I’ll often do because I like close reading – your own screen splits to show

both the text and your conference colleagues

side-by-side. Mine won’t. But because I’m using multiple screens, I can drag the

window-in-a-window in which you all appear onto another screen and then enlarge

it by dragging, and that takes me a moment to do. Clunky clunky

clunky.

·

I’ve

compiled a set of ten online commandments that I’d like you to review – they’re

on our Moodle page – and I’d appreciate your own input here. Since drafting that list, I’d like to add a couple more here (with all due apologies to the

original drafter of commandments who apparently thought they should come in tens):

o I’ve had

mixed results with break-out rooms and tend not to use them, but we’re not a

huge group and so probably won’t need them. Yet on the days when you and your

colleagues are leading conferences, you can by all means use

them if you want, and I’ll transfer “host” controls over to you.

o Please

don’t assume I’ll ever see the chat box. I have one

eye on my screen and another on my notes, and while we’re

studying Buddhism, I have yet to develop a third eye.

o If you’ve had me before, you already know that I never put

people on the spot and usually solicit input from the conference in general

unless in our conference preparations you’ve been explicitly asked to prep

something in particular. There may be times that you may need to have your

camera off – and that’s fine – but please note that I’ll never call on anyone I

can’t see unless you’ve emailed me in advance to say

“My camera must be off but I’m present and participatory, happy to engage and

be called upon.” (Before you simply opt for always “camera off,” please

remember that, like most conferences at Reed, participation is indeed an

evaluated requirement – see below.)

·

Finally we’ll observe a “spring break” on March 10 and 12

because I realize that constant focus without some kind of pause will make

zombies of all of us.

This

year I’m just as much of a student as you are. I’ll try my best, and I’ll need your help.

IV. Resources

A. Required texts in the

bookstore

·

Watson,

Burton (trans.). The Lotus sutra (New

York: Columbia University Press, 1993).

·

Watson,

Burton (trans.). The Vimalakirti

sutra (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

“But

I thought this was a sutra-reading course – why are we only buying a couple of

them?” I’m glad you asked. Bukkyō

Dendō Kyōkai

(BDK) at Berkeley is the hub of sutra translation, and they hire the best

scholars in academia to do their translations. Except for the above three

texts, all the rest of our scriptures come from them. You can buy the BDK

editions we’ll read on Amazon – I have myself because

I like scribbling in physical books – but BDK, being a Buddhist organization wanting

to spread the dharma, also offers all its publications for download free of

charge. Simply go to their website:

https://bdkamerica.org/tripitaka-list/

This semester you’ll

want to download the following five books (full citations in the bibliography

at the end of this syllabus):

·

Apocryphal

scriptures

·

Baizhang Zen

monastic regulations

·

Buddhacarita: In

praise of Buddha’s acts’

·

Pratyutpanna samādhi sutra/Śūrangama

samādhi sutra

·

Three

Pure land sutras

Downloads aside, if money is an issue there’s a small number of copies in the Religion student lounge (2nd floor ETC, door code 256980) on a bottom shelf of the south wall labeled “Brashier’s books.” For example, there’s several copies of BDK Three Pure land sutras and Apocryphal scriptures there. That shelf also has copies of texts from both my pre-imperial and early imperial introductory courses. Please let students with significant financial need have first shot at them, but by the end of the first week, it’s open season for everyone. The books on that shelf are free, and I don’t need them back.

B.

Supplementary texts – very important so please read!

Let

me add here two very useful supplementary texts, especially if you’re relatively new to Buddhism:

·

Williams,

Paul. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The doctrinal foundations, 2nd

ed. (London: Routledge, 1989).

·

Lopez,

Donald. The story of Buddhism (San

Francisco: Harper, 2001).

The

former is the best secondary source on Mahāyāna Buddhism (the main form of Buddhism in

China) and will offer you solid context for all the sutras we’ll

read. (If you seek a copy, make sure you get the second edition.) The latter is

a very readable general survey of Buddhism, and this is available in the

bookstore (under “Religion 116” because I’m teaching

it in my intro this semester) or on Amazon.

Regarding Lopez…. The first

several weeks of this course will be painfully slow, the readings for each

conference very short but very complicated if you’re

new to Buddhism. We’ll carefully pace ourselves, and

I’ll try my best to give you a sturdy foundation of “first principles.” (For

example, recall my note about the “piton presentations” above.) While you’ll need to spend a lot of prep time thinking about these

short sutra chapters, this might also be a good opportunity to bulk out your

general Buddhism knowledge. You might spend your extra reading time with Lopez,

and if you want, I can offer weekly Q&A sessions outside of conference time

– maybe a group of you might want to come to my office hours – and I can answer

any questions you have about Buddhist basics. (I’ve

also made some videos on Buddhist basics I’ll post on our Moodle page.) Let me

know if that sounds like a good idea, and you can coordinate with others who

might likewise benefit from a refresher in Buddhism’s basics. I leave that up

to you.

C.

Reference texts

·

Buswell,

Robert E. and Donald S. Lopez. The

Princeton dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press, 2014). Published in 2013, this

huge resource is very useful for basic terms, and you can access an electronic

version of it via the Reed library website.

·

Gethin,

Rupert. The foundations of Buddhism

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

·

Lopez,

Donald. Critical terms for the study of

Buddhism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

·

Yü

Chün-fang. Chinese Buddhism: A thematic history (Honolulu: University of

Hawai’i Press, 2020). Note the date.

D.

Moodle

There is an extensive Moodle site for this course, the “Ereserves” all in a folder at the top. I suggest saving this on your browser toolbar:

https://moodle.reed.edu/course/view.php?id=3423

The Moodle site will also include links to audios/videos and any documents we develop during this course. (Because I truly want this to be a group discussion with myself part of your group rather than the sagely teacher telling you “What’s what,” I do not intend to stock Moodle with my “reading maps” which I’ve done in all my other courses, but if you find them helpful, I can change this plan.)

V. Requirements

A.

Active and informed conference

participation.

Please note that active participation every day is intrinsic to this course,

and please be fully prepared for each conference, preparation consisting of

both reading and thinking about the materials. Your full preparation

really helps me out a lot in this year of online teaching and makes conference

much more pleasant all around. (I’ve noticed that

“participation” really takes a hit in online teaching, any silences deafening. The

real distance between people decreases the pressure to participate, and we tend

not to talk to our TVs, the cousin of Zoom.) Keep in mind that it’s “participation” that leaves the biggest impression in

your teacher’s head because your participation – not your papers, not your

group projects, etc. – is what’s helping your teacher run the course.

Appended to this syllabus are some suggestions on conference dynamics, and if

conference isn’t going well, please talk to me. We

will endeavor to remedy the situation with concrete changes. At the very

least, I recommend every day homing in on a particular passage that “speaks” to

you, that gives you insights and leads us to good group discussions. I much

value close reading, and I love it when we jump from passage to passage,

developing a conference theme that draws on the textual and material evidence

at hand. That’s an easy, simple way to have something

to contribute to every conference.

B.

Shorter

informal writing activities.

Many of you are familiar with what I call “exploratories”

(an explanation for which is also appended to this syllabus), and I will often

ask you to contribute a short argument in writing (usually just a single-spaced

page) to our progress. These are not scheduled on the syllabus simply because,

as noted above, there’s no “schedule” and I’m

uncertain how fast we will proceed through the materials. Yet you can assume an

informal, low-stakes writing assignment at least every

other week. Unlike my introductory courses, these will not be due in advance of

conference, but of course you will be expected to contribute your ideas

accordingly to that day’s discussion. While I can’t give you precise days on

which these low-stakes writing assignments will be

due, I can give you some examples:

o When we reach the “Grotto of

complete enlightenment,” I will ask each of you to take one of the ten

bodhisattvas featured therein and summarize the argument to begin our

discussion of him or her. (Even though each of these ten “chapters” are only

four or five pages in length, this is much

harder than it sounds!)

o Or when we get to the Lotus sutra, I’ll

simply ask you to contribute an exploratory on any theme you think the

conference should discuss. (Alternatively, I might ask you to approach the

sutra with either a philosophical, religious or

literary lens in particular.)

o Or when we get to the

Bodhidharma anthology, I’ll ask you to connect two or

three of its independent passages to construct a coherent argument.

The main goal of short writing assignments (as you will see

in the exploratory explanation appended) is simply to foster good, meaty

conversation based on a close reading of the texts.

C.

Longer formal writing

assignments,

namely three papers (5-8 pages). As mapping is our course’s allegory, I want

you to map out an ongoing theme of your choice throughout this course. That is,

I would like you to “own” an idea, making a note of it whenever you come across

relevant material. Your first paper will for the most part justify your choice

of theme using this semester’s initial readings (i.e.

justify your topic); your second will chart out that idea via the texts we’ve

encountered by the time that paper is due (i.e. formulate your thesis); and

your third will of course complete the map and describe your destination (i.e.

draw your conclusions). Throughout, I hope you will develop an original

understanding or argument regarding your chosen theme. Below I list a large number of options, all of them major themes in

Mahayana Buddhism and for the most part easy to track through our sutras. Most

are in fact a bit too big, and many overlap even if the emphasis of each is different. You need

not list every single reference to your map’s theme, and you may narrow down

that theme where necessary (as long as you include all

the major passages still relevant to your narrowed theme). I am happy to meet

with you to discuss choices, and you are welcome to make an argument for a

topic not on this list (although I might be disinclined if I know the evidence

will be too limited in the forthcoming sutras). Options for your map include:

|

Self |

The Buddha |

Practice, devotion

and experience |

|

Cosmos |

Discursive logic |

Emptiness |

|

The laity |

Merit earning and trafficking |

Behavior (e.g.

the six paramitas) |

|

Desire |

The sangha |

The path to becoming a bodhisattva |

|

Conventional versus ultimate

reality |

The nature of enlightenment |

Compassion |

|

Sutra language / sutras about “language” |

The Buddhist psyche |

Nirvanas and Pure Lands |

The paper deadlines are here somewhat arbitrary simply

because I don’t know how far along the cliff we will

have ventured, but even so, they are roughly as follows so you can plan

accordingly:

o The first at the end of 5th

week: Saturday, 27 February (midnight);

o The second at the end of 9th

week: Saturday, 27 March (midnight);

o The third in the reading/examination

weeks: 7 May (for comments) or 13 May (without comments). Note that no work is

accepted after 5 p.m. on 13 May.

When submitting your paper, please use .doc/.docx (if

possible) because I can then use the MSWord “Review/Track changes” function for

comments and can also use the “Read aloud” function to keep me focused.

D.

The Buddhist basics. Please expect a short exam

after our first sutra just to make sure we all have the basic vocabulary down.

E.

A group project. Because the pandemic hampers in-person gatherings, there is

no group project this year.

VI. Incompletes, absences, accommodations, extensions – the draconian

stuff so PLEASE READ

As the great early Chinese legalist Han Feizi warned, indulgent parents have rowdy kids, and overly lenient

rulers have inefficient subjects. By extension, a permissive teacher can’t maximize a student’s learning potential. By laying

down the law now, we’ll also never need to raise it

again in the future, and I can pretend to be a kindly Confucian rather than a

draconian legalist.

“An Incomplete [IN] is permitted in a

course where the level of work done up to the point of the [IN] is passing, but

not all the work of a course has been completed by the time of grade

submission, for reasons of health or extreme emergency, and for no other

reason,” according to the Reed College Faculty Code (V A). “The decision

whether or not to grant an IN in a course is within the purview of the faculty

for that course.” Like many of my colleagues, I read this as restricting

incompletes to acute (not chronic), extreme emergencies and health crises that

have a clear beginning date and a relatively short duration only, that are

outside the control of the student, and that interrupt the work of a student

who was previously making good progress in a course. Needless to say, we’ll be a bit more tolerant during the pandemic

pause, but incompletes still aren’t automatic and must be justified. Now more

than ever, we all need things we can depend on, and in teaching, we can benefit

by maintaining our expectations regarding the timeliness and quality of our

work. You must stay in communication with me if there’s

a problem in participation, papers or presentations.

Regular, prepared, and disciplined

conferencing is intrinsic to this course, and so at a certain point when too

many conferences have been missed – specifically eight which translates into a “fail” for the course – it would logically be advisable to

drop or withdraw.[6]

There’s no shame in that. Longer-term emergencies indeed happen, and you ought

to make use of Student Services when they do. In sum, I’ll

help you out as much as I can to get you across the finish line, but as already

noted, it’s the same finish line for everyone and to be fair to your colleagues

I need to have you there in the race. To that end, I would ask that you please email me whenever you are absent just

to let me know you’re okay. (More and more students

seem to be doing this without prompting anyway, perhaps because we’ve all become increasingly dependent upon virtual

connectivity.)

I’m

happy to give paper extensions for medical problems and emergencies, and you

should take advantage of the Health and Counseling Center in such

circumstances. I’m well aware that, during the

pandemic pause, we’ll need to be more flexible, and as already noted, we can

try to find accommodations to make up for gaps that might occur. But out of

fairness to everyone, “not doing the work” can’t be

one of those accommodations. Please note that here, too, the honor principle

provides a standard for expectations and behavior, meaning that none of us

(including myself) should resort to medical reasons when other things are actually impeding our work. (Please just be honest. It’s as simple as that.) In non-medical situations, late

papers will still be considered (except for the 13 May deadline), but the

lateness will be taken into account and no comments

given. Ken’s Subjectivity Curve: The later it is, the more subjective Ken

becomes. It's a gamble. I’m

not a legalist like Han Feizi, but even the

Confucians resorted to hard law when ritualized conduct and exemplary

leadership failed.

|

|

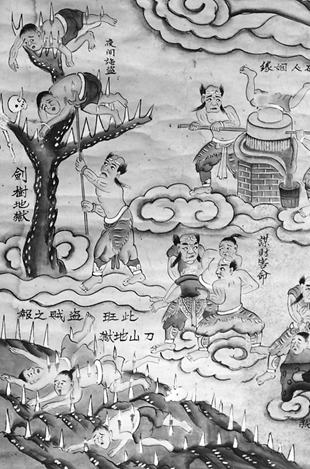

Karmic retribution for poor participation in conference…. (from Ken’s hellscrolls.org) |

VII. The

syllabus ... The map

There’s a simple, practical reason why

I’ve opted for a spatial allegory instead of resorting to normal calendrical

parameters when organizing this syllabus: I don’t know how much time we will need

to spend below each set of Dazu’s cliff-face images. This is not a “It’s

Thursday, so it’s Beijing” itinerary, and if we need more time with particular sutras or less time discussing particular

problems, then we can adapt accordingly, especially given the fact that we’re a

small group. This unique approach perhaps merits a couple extra observations:

A. I don’t

intend to make it through the full site. Dazu is simply too rich and

comprehensive in its textual allusions, and so it’s

okay if we don’t reach the exit.

B. If you say at some point “Let’s spend

more time here!” instead of moving on to the next sutra, that’s

fine. Alas, that doesn’t mean your conference

preparations get reduced. As noted above, I may then ask you to devote your

prep time (aside from further thinking about the sutra directly at hand) to

continuing your secondary reading about the Mahayana tradition in general. (Specifically in “IV. Resources” above, I drew your attention

to the secondary studies of Donald Lopez and Paul Williams.) I might say something

like “Okay then. In lieu of proceeding to the next stop on the map, please continue

Williams by reading pp. n-n.” I generally don’t intend to discuss Williams in

conference, but if you think there are issues therein

we ought to tackle, by all means please raise them in our discussion.

C. The scholar-monk Zhao Zhifeng isn’t entirely dictating our syllabus structure. In fact, I’ve taken certain pedagogical liberties in terms of where

we’re beginning our tour and exactly where we’re stopping along the path. As to

the former, I want to begin in the cave dedicated to the Sutra of perfect enlightenment (or Sutra of full awakening, the Yuanjue jing 圓覺經)

– No. 5 on the map below – because I think this sutra is a great basic

catechism for Chinese Buddhism. To me, it looks like an intentionally organized

“basics of Buddhism” statement written by a Chinese scholar for a Chinese

audience, and I admit to being exceedingly fond of it. As to our selectivity in

the stops along the path, I’m naturally favoring the sites that directly allude

to the major sutra traditions, but if you see images where you would like us to

tarry – and I can loan you books on Dazu so you know where

(literally) we always are – just say the word. I can probably find texts to go

along with that set of sculptures.

And

one final observation about resorting to this spatial allegory: I’m not the tour

guide. I’m neither Buddhologist

nor Buddhist and am just a student who’s intensely fascinated by Chinese

Buddhist ideas. Think of me as a fellow visitor to Dazu, and we’re

all going to learn the landscape together.

The numbered subheads in the

following itinerary correspond to the “topic” numbers on our Moodle page. The

links to BDK downloads, to videos, to external URLS, etc., can all be found

under the corresponding Moodle topic number, too. Ereserves

are all in the folder at the top of the Moodle page.

1. Introduction: Heading straight for a cliff….

2. An important caveat about our

“travel guides”: The problem of textocentrism

o Nattier, “The proto-history of

Buddhist translation: From Gandhari and Pali to Han-dynasty Chinese” (Moodle.)

This is supplemental but please at least read my summary.

o Blackburn, “The text and the

world,” 151-167. (Moodle.)

o Wu, “From the ‘Cult of the book’

to the ‘Cult of the canon,” 46-78. (Moodle.)

o Fang, "Appendix: Defining

the Chinese Buddhist canon: Its origin, periodization, and future,"

187-215. (Moodle.)

3. Figuring out how to read the map…

·

“Laozi’s

argument, where it came from, and where it’s going” (three-part video). (Moodle.)

·

“An

introduction to Buddhism, selfhood and dolls” (three-part video). (Moodle.)

·

Williams,

“Introduction,” 1-44. (Moodle.)

·

The

diamond sutra: http://www.acmuller.net/bud-canon/diamond_sutra.html.

·

Venerable

You Yong, The Diamond sutra in Chinese culture, 156-170 (note the page

numbers as the pdf is longer). (Moodle.)

·

Kieschnick, The impact of Buddhism on Chinese material culture,

164-185. (Moodle.)

·

Brashier,

“Why was the Diamond sutra associated with hell since early medieval

China? (Moodle.)

4. ... and we walk into Dazu...

·

Kucera,

Ritual and representation in Chinese

Buddhism, 1-13, 31-54, 251-264 (note stopping point). (Moodle.)

·

Dazu

image database (Moodle.)

·

Site

summary: http://www.art-and-archaeology.com/china/baoding/ba01.html

Dazu site: The circled numbers are our syllabus stops and

Moodle numbers,

the smaller numbers are page references in Howard, Summit

of treasures.

|

Grotto of Complete Enlightenment (DeBing

photography) |

5. ... beginning in its “Grotto

of Complete Enlightenment.” ·

Muller,

The sutra of perfect enlightenment,

3-16, 40-46. (Moodle.) ·

Gregory,

The sutra of perfect enlightenment,

in Apocryphal scriptures, 51-125. (BDK

download.) ·

Muller,

The sutra of perfect enlightenment,

70-85. (Moodle.) (Please

expect an exam on the fundamental vocabulary of Chinese Buddhism upon our exit

of this cave.) |

|

|

6. Eastward to “The three

worthies of Huayan” ·

Williams, “Huayan – the flower garland tradition,” 129-148. ·

Fontein, The pilgrimage of Sudhana,

1-22. (Moodle.) ·

Cleary (trans.), The Flower ornament scripture, 1135-1182. (Moodle.) ·

Cleary (trans.), The Flower ornament scripture, 1452-1518. (Moodle.) |

The three worthies of Huayan

(with raindrops) |

|

|

Thousand-handed, thousand-eyed Avalokitehsvara |

7. Eastward to

“Thousand-handed, thousand-eyed Avalokitehsvara” ·

“The

Lotus sutra: Ananda’s second report” (three-part video). (Moodle.) ·

The Lotus sutra. (Book.) |

|

|

8. Turning northward to the

life and death of the Buddha ·

Buddhacarita:

In praise of the Buddha’s acts. (BDK download.) ·

Zürcher, “Chih Tun’s introduction to

his ‘Eulogy on an image of the Buddha Sākyamuni’,”

177-179, 381-385. (Moodle.) ·

“A

brief biography of the Buddha,” from The

Baizhang Zen monastic regulations, 41-45. (BDK

download.) |

The Buddha entering Nirvana |

|

|

Images of filial kindness |

9. Turning westward to “The

Buddha Shakyamuni repaying his parents’ kindness” ·

The sutra of forty-two

sections, in Apocryphal scriptures, 29-46. (BDK

download.) ·

The sutra on the profundity of

filial love,

in Apocryphal scriptures, 129-139. (BDK

download.) ·

Mollier, “Karma and the bonds of kinship in medieval Daoism:

Reconciling the irreconcilable,” 171-181. (Moodle.) |

|

|

10. Westward to “The Land of Bliss

of Buddha Amitayus” ·

The Pratyutpanna

samadhi sutra.

(BDK download.) ·

The Surangama

samadhi sutra.

(BDK download.) ·

The three Pure land sutras. (BDK download.) ·

Dunhuang Pure Land images (Image set on

Moodle.) |

Born in lotus flowers in the Land of Bliss |

|

|

The oxherding parable for Chan

contemplation (see Howard, 66-71) |

11. Westward to the “Six roots

of sensations” ·

“Chan

Buddhism and the Platform sutra” (three-part video). (Moodle.) ·

Broughton,

The Bodhidharma anthology. (Book.) ·

McRae,

“The hagiography of Bodhidharma,” 125-138. (Moodle.) ·

The

Vimalakirti sutra (Book). ·

Shohei, The Baizhang Zen monastic regulations,

23-45, 225-48, 286-319.

(BDK download.) |

|

|

12. Westward to the hell

tribunals ·

The Ullambana

sutra, in Apocryphal scriptures, 19-25. (BDK

download.) ·

Faure,

“Indic influences on Chinese mythology: King Yama and his acolytes as gods of

destiny,” 46-60. (Moodle.) ·

Anonymous,

“Transformation text on Mahamaudgalyayana rescuing

his mother from the Underworld,” 1093-1127. (Moodle.) ·

Study collection: www.hellscrolls.org. |

Arrested and awaiting hell’s tortures |

|

VIII.

Consciousness of conference technique

Much of our educational system

seems designed to discourage any attempt at finding things out for oneself, but

makes learning things others have found out, or think they have, the major

goal. – Anne Roe (American clinical psychologist),

1953.

At times it is useful to step back and discuss conference dynamics, to lay bare the bones of conference communication. Why? Because some Reed conferences succeed; others do not. After each conference, I ask myself how it went and why it progressed in that fashion. If just one conference goes badly or only so-so, a small storm cloud forms over my head for the rest of the day. Many students with whom I have discussed conference strategies tell me that most Reed conferences don't achieve that sensation of educational nirvana, that usually students do not leave the room punching the air in intellectual excitement. I agree. A conference is a much riskier educational tool than a lecture, and this tool requires a sharpness of materials, of the conferees and of the conference leader. It can fail if there is a dullness in any of the three. Yet whereas lectures merely impart information (with a “sage on the stage”), conferences train us how to think about and interact with that information (with a “guide on the side”). So when it does work....

The content of what you say in conference obviously counts most of all, and so how do you determine in advance whether you’ve got something worthwhile to say? First, read proactively rather than passively, and don’t just quickly read the assigned materials. Mark up the text as you go, although the problem with our BDK downloads is that you’ll be dissuaded from marking up screen-based texts. You might want to either print them out or invest in a .pdf annotating application. After you’ve read it and marked it up, then take a couple minutes to analyze it. But how do you analyze it? A colleague and friend at Harvard, Michael Puett, writes, “the goal of the analyst should be to reconstruct the debate within which such claims were made and to explicate why the claims were made and what their implications were at the time.” A religious or philosophical idea doesn’t get written down if everyone already buys it; it’s written down because it’s news. As new, we can speculate about what was old, about what stimulated this reaction. Think of these texts as arguments and not descriptions, and as arguments, your job is to play the detective, looking for contextual clues and speculating on implications. I will give you plenty of historical background, and if you look at these texts as arguments, you will get a truer picture.

In addition to content, there are certain conference dynamics that can serve as a catalyst to fully developed content. I look for the following five features when evaluating a conference:

A. Divide the allotted time by the number of conference participants. That resulting time should equal the leader's ideal speaking limits. I know I talk too much in conference, but when I say this to some students, they sometimes tell me that instructors should feel free to talk more because the students are here to acquire that expertise in the field. So the amount one speaks is always a judgment call, but regardless, verbal monopolies never work. I honestly feel bad after a “crickets” conference – when after soliciting everyone’s input I only hear crickets – and while I might be able to regale everyone with lots of data and insights, it’s not the “conferring” of conferencing.

B. Watch the non-verbal dynamism. Are the students leaning forward, engaging in eye contact and gesturing to drive home a point such that understanding is in fact taking on a physical dimension? Or are they silently sitting back in their chairs staring at anything other than another human being? As a conference leader or participant, it's a physical message you should always keep in mind. Leaning forward and engaging eye contact is not mere appearance; it indeed helps to keep one focused if tired. In online teaching, the cues are harder to discern but still present. Usually it’s the absence of cues – the always-off-camera “participant,” the on-camera sleeping participant, the on-camera participant who clearly fails to react to something when everyone else did. (All these happened last semester.)

C. Determine whether the discourse is being directed through one person (usually the conference leader) or is non-point specific. If you diagram the flow of discussion and it looks like a wagon wheel with the conference leader in the middle, the conference hasn’t worked well. If you diagram the flow and it looks like a jumbled, all-inclusive net, the conference is more likely to have succeeded.

D. Determine whether a new idea has been achieved. By the end of the conference, was an idea created that was new to everyone, including the conference leader? Did several people contribute a Lego to build a new thought that the conferees would not have been able to construct on their own? This evaluation is trickier because sometimes a conference may not have gone well on first glance but a new idea indeed evolved nonetheless. The leader must be sure to highlight that evolution at conference end.

E. Watch for simple politeness. “Politeness” means giving each other an opportunity to speak, rescuing a colleague hanging out on a limb, asking useful questions as well as complimenting a new idea, a well-said phrase, a funny joke. (Politeness is not allowing an endless silence with no one jumping in, the crickets quietly chirping away. Total silence tells me I totally screwed up in guiding that part of the discussion.)

If you ever feel a conference only went so-so, then

instead of simply moving on to the next one, I would urge

you, too, to evaluate the conference using your own criteria and figuring out

how you (and I) can make the next one a more meaningful experience. As noted, preparation is not just reading the

assigned pages; it’s reading and then thinking through

something in that reading, developing a thought and getting it ready to

communicate it to someone else.

At the very least, habituate yourself to having a passage you’d like us to discuss or a relevant question you think might foster a meaningful meeting of minds. In the end, as long as you are prepared and feel passionate about your work, you should do well, and if passion ever fails, grim determination counts for something.

IX. The

exploratory

Sometimes conferences sing. Yet just when I would like them to sing glorious opera, they might merely hum a bit of country-western. After my first year of teaching at Reed, I reflected upon my conference performance and toyed with various ideas as to how to induce more of the ecstatic arias and lively crescendos (and have everyone join in the chorus), and I came up with something I call an “exploratory.”

Simply put, an exploratory is a one-page, single-spaced piece in which you highlight one thought-provoking issue that caught your attention in the materials we are considering. This brief analysis must show thorough reading and must show your own thoughtful extension –

· Your own informed, constructive criticism of the author (and not just a bash-and-trash rant);

· Your own developed, thoughtful question (perhaps even inspired by readings from other classes) that raises interesting issues when seen in the light of the author's text;

· Your own application of theory and method to the primary source;

· Your own personal conjecture as to how this data can be made useful; or (best of all)

· Your own autonomous problem that you devised using the same data under discussion.

I am not here looking for polished prose or copious (or any) footnotes – save all that for our formal papers. These are lower-stakes writing assignments intended to foster conference quality rather than to be submitted to the Pulitzer commission. (I don’t even return exploratories with comments unless a special request is made.) In medicine, an exploratory is not full, open-heart surgery performed on the text. Instead, exploratories tend to be somewhat informal but focused probes on one particular aspect in which you yourself can interact with the text and can enter into the conversation. You need to make a point.

What is not an exploratory? It is not merely a topic supported by evidence from the book, nor is it a descriptive piece on someone else's ideas, nor is it a general book report in which you can wander to-and-fro without direction. Bringing in outside materials is allowed, but the exploratory is not a forum for ideas outside that day's expressed focus. (Such pieces cannot be used in our conference discussions.) Also, don’t give into the temptation of just reading the first few pages of a text and then writing your exploratory. (If you were the teacher, what would you conclude if you received a lot of exploratories that all coincidentally tackled an issue that came up within the first five or six pages of the reading?) It is instead a problematique, an issue with attitude.

The best advice that I can give

here is simply to encourage you to consider why

I am requesting these exploratories from you: I want

to see what ignites your interest in the text so I can set the conference agenda based on your interests. As noted above, I won’t

require them the evening before like I do for my introductory courses, although

they must be sent to me (embedded in an email, not as an attachment)

before conference begins. Thus you get the advantage

of more time to write them. The disadvantage is, I’ll

be relying upon you to make your point without prompting during the conference

discussion itself.

Late exploratories are of no use. (Being handed a late exploratory is like being handed your salad after you've eaten dessert and are already leaving the restaurant.) I will use your contributions to draw you in, parry your perspective against that of another, and build up the discussion based on your views. Exploratories help me turn the conference to perspectives that directly interest you. They often lead us off on important tangents, and they often return us to the core of the problem under discussion. So if you are struggling with finding “something to say,” simply recall why I ask for these exploratories in the first place. Is there something in the text you think worthy of conference time? Do you have an idea you want to take this opportunity to explore? Here is your chance to draw our attention to something in the text the rest of us might not have noticed. Your perspectives are important, and if you have them crystallized on paper in advance, they will be easier to articulate in conference.

Since I began using exploratories, most students have responded very favorably. Students like the fact that it is a different form of writing, a bit more informal and more frequent, somewhat akin to thinking aloud. It forces one not just to read a text but to be looking for something in that text, to engage that text actively. And it increases the likelihood that everyone will leave the conference singing Puccini.

X. Bibliography

“Transformation text on Mahamaudgalyayana rescuing his mother from the Underworld,” in The Columbia anthology of traditional Chinese literature, Victor Mair, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 1093-1127.

Blackburn, Anne M. “The text and the world,” in The Cambridge companion to religious studies (2012), 151-167.

Broughton,

Jeffrey L. (trans.). The Bodhidharma

anthology: The earliest records of Zen (Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press, 1999).

Buswell, Robert E. and Donald S. Lopez.

The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

Cleary, J.C., et al (trans.). Apocryphal scriptures (Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, 2005).

Cleary, Thomas. The Flower ornament scripture (Boston: Shambhala, 1993.

Fang Guangchang. "Appendix: Defining the Chinese Buddhist canon: Its origin, periodization, and future," in Reinventing the Tripitaka: Transformation of the Buddhist canon in modern East Asia (Lexington Books, 2017), 187-215.

Faure, Bernard. “Indic

influences on Chinese mythology: King Yama and his acolytes as gods of

destiny,” in India in the Chinese

imagination: Myth, religion, and thought, John Kieschnick

and Meir Shahar, eds. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014),

46-60.

Gethin, Rupert. The foundations of Buddhism (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1998).

Harrison, Paul and John McRae (trans.). The Pratyutpanna samadhi sutra and The Surangama samadhi sutra (Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, 1998).

Ichimura Shohei (trans.). The Baizhang

Zen monastic regulations (Berkeley, CA: Numata

Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, 2006).

Inagaki Hisao (trans.). The three Pure land sutras

(Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation

and Research, 1995).

Jan Fontein.

The pilgrimage of Sudhana: A study of Gandavyuha illustrations in China (De Gruyter Mouton,

1967 [reprint 2012]), 1-22.

Kieschnick, John. The impact of Buddhism on Chinese material culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003).

Kucera, Karil. Ritual and representation in Chinese Buddhism (Amherst, NY: Cambria press, 2016).

Lopez, Donald. Critical terms for the study of Buddhism

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Lopez, Donald. The story of Buddhism (San Francisco:

Harper, 2001).

McRae, John R. “The hagiography

of Bodhidharma: Reconstructing the point of origin of Chinese Chan Buddhism,”

in India in the Chinese imagination:

Myth, religion, and thought, John Kieschnick and

Meir Shahar, eds. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014),

125-138.

Mollier, Christine. “Karma and the

bonds of kinship in medieval Daoism: Reconciling the irreconcilable,” in India in the Chinese imagination: Myth,

religion, and thought, John Kieschnick and Meir

Shahar, eds. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), 171-181.

Muller, A. Charles. The sutra of perfect enlightenment: Korean

Buddhism’s guide to meditation (Albany: State University of New York Press,

1999), 3-16, 40-46.

Muller, A. Charles. The sutra of perfect enlightenment: Korean Buddhism’s guide to meditation (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999), 70-85.

Watson, Burton (trans.). The Lotus sutra (New York: Columbia

University Press, 1993).

Watson, Burton (trans.). The Vimalakirti sutra (New

York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

Willemen, Charles (trans.). Buddhacarita: In praise of Buddha’s acts (Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, 2009).

Williams, Paul. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The doctrinal foundations, 2nd

ed. (London: Routledge, 1989).

Wu, Jiang. “From the ‘Cult of the book’ to the ‘Cult of the canon,” in Spreading Buddha’s word in East Asia (2016), 46-78.

Yong You, Venerable. The Diamond sutra in Chinese culture (Los Angeles: Buddha’s light publishing, 2010).

Yü Chün-fang. Chinese Buddhism: A thematic history (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2020).

Zürcher, E. The Buddhist conquest of China: The spread and adaptation of Buddhism in early medieval China: Text (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1972).

Dazu’s wheel of transmigration – where are you going on your

next trip?