|

Rel. 310: Death, hell and rebirth in Chinese history “A tour of the byways of the unseen realm, so that you will know of the retribution that follows upon sins….” – From the 5th century Mingxiang ji 冥祥記 |

K.E. Brashier ETC 203 Office hours: M 10-11, F 11-noon Spring 2017 |

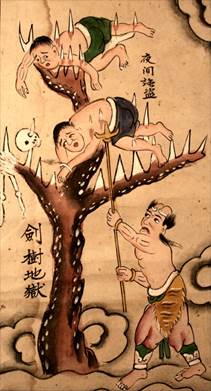

Religious communication navigates between “imagistic” and “doctrinal” modes of religiosity,[1] between painture and parole that within the Western discourse have been regarded as the two “portals to the house of memory” ever since the thirteenth century. This course will utilize both of these portals as we focus on death – and more particularly, on hell – in late imperial China. In terms of painture, Chinese “hell scrolls” (dìyù juànzhóu 地獄卷軸) depict the bureaucratic underworld courts where sinners are tortured and viewers are treated to a morality play; they are an amalgamation of ethics, entertainment and an education on how the cosmos works, their purpose being to warn us about the certainties of karmic retribution. In this course, we will not only analyze the world’s largest online collection of such scrolls (our own!), we will also be contributing to the global knowledge of this genre by each of us producing original high-quality teaching videos to be incorporated into this website (www.hellscrolls.org).

In terms of parole, this course is also devoted to mastering the long textual tradition of visits to hell, beginning in the 2nd century BCE and ending in the 20th century CE. Some of these visits are three pages long; others are three hundred pages long. From sutras to fine literature, from opera scripts to popularly produced morality books, these textual encounters with hell will in turn inform our teaching videos, ensuring that they will be meaty contributions to the field of scholarship. We will of course be reading several available secondary studies on Chinese hell (and we’ll read some theory to apply to it as well), but the bulk of our reading in this course will be primary sources in translation.

I. Overview: A

long tradition on images and texts about hell

For most of its imperial history, China’s traditional entrance to hell has been at Fengdu, now a tourist town that in recent years has boasted dark dungeons filled with life-sized automatons being tortured under the angry gaze of the underworld’s ten kings. Yet Fengdu’s hell has fallen upon hard times, and the last time I was there, I saw demons covered in thick dust, their weapons missing from broken hands. A headless corpse rose out of his coffin, but his headless-ness was only because the wooden neck had snapped, his head still lying inside the coffin. Hell had gone to hell.

The two-dimensional representations of hell on hanging scrolls have not fared much better than their three-dimensional cousins. They have a long history, their earliest predecessors ranging from simply painted hand scrolls to elaborate artistic wall scrolls from the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties respectively. They also have a rich contextual frame, from scores of texts about visiting hell to annual rituals giving respite to the damned and even to extremely famous folk operas that double as village exorcisms. Yet a combination of modernity, the Cultural Revolution and a disregard for these tattered-and-torn religious tools (rather than seeing these painted scrolls as artworks in their own right) has resulted in the loss of almost the whole genre. Our own collection of one hundred and thirty-three hell scrolls from the 18th to 21st centuries is merely a tiny remnant of a once-grand tradition.

The hell scrolls in our collection[2] range from cartoonish folk art to elaborate, painterly canvases, but most are hand-painted images that were manufactured at production-line artisan workshops. (We will pause to consider their production techniques as well.) Amidst the variety of styles and compositions, there are thematic constants. The first scroll depicts a sinner’s entrance into hell where his or her life is reviewed and punishments duly assigned; the last scroll is overseen by the Wheel-turning King as the now-tortured soul is allocated one of six forms of rebirth. In between, these scrolls not only chart the dead’s torturous journey, they reveal what people worried about, from arson, murder and theft to gossipy neighbors, corrupt officials and farmers who neglected to clean up after their livestock. In other words, these scrolls aren’t just about the “otherworld”; they also provide a unique access point to the world of the living in late imperial China – to their anxieties, their ethics and their stories.

What makes the Chinese hell scrolls special – and what first attracted me to this genre – is that they themselves combine painture and parole in their educating the laity and enforcing an ethic. Displaying both pictures and texts (the latter in the form of cartouches, couplets and admonishments), they merge the provocative, colorful aesthetics of the grotesque with the grander canonical message of karmic retribution that was well known from narratives and sutras. They force us to rethink our assumptions about how these media separately functioned to communicate a religious doctrine.

Stephen Teiser, author of The scripture on the ten kings and other works on Chinese hell, writes, “The Chinese Buddhist understanding of purgatory should also be a part of an unfortunately neglected side of Buddhist studies, the investigation of beliefs and practices distributed widely across a given culture.” Even though belief in these hells spanned most social classes, most regions and most religions in late imperial China, study of them has remained sparse. Our course will attempt to address this lacuna in Chinese and religious studies, not just for ourselves but – with the production of our teaching videos – for the rest of the world as well.

II.

Requirements

As you probably already know, this course will

probably be like no other course you’ve taken because

you won’t just be absorbing information about the colorful fiery realms of

Chinese hell, you’ll also be producing something real and tangible to teach

your colleagues across the world and into the future.

Our online study

collection of Chinese hell scrolls is used internationally, serving as (for

example) the basic introduction to Chinese underworld gods in Columbia

University’s “Asia for educators” website. Eileen Gardiner references us both

in her Buddhist hell anthology (which

we’ll be reading) as well as on her own website.

Stephen Teiser (a Princeton professor cited above and we’ll be reading one of his books, too) uses it

for his own undergraduate teaching purposes. Yet as well trafficked as it may

be, our website lacks an enjoyable-yet-thorough introduction to this

fascinating religious phenomenon. It’s a bit ... flat. As a group and with extensive

support from Computer and Information Services (CIS), we will remedy this

flatness by creating a playlist of high-quality teaching videos to introduce

this site to future visitors. I envision the resulting playlist as a resource

that teachers can assign as homework for their students, each teaching video on

that playlist introducing through visual image and spoken word a fundamental

feature of the late imperial Chinese hells. As you will see on the schedule

below, CIS will spend much time teaching us how to make high quality teaching

videos, and with their help, we will draw upon our thousands of images – all

for which we ourselves possess the copyright – and at the same time I will

spend this semester leading you through scores of primary sources so that, in

the end, you will have plenty of texts to marry to those images.

Hence in terms

of course requirements, many of them will be unique in nature. I’ll still

resort to several of my “standards” (e.g. exploratories), but in no other course have I ever included

“storyboards” and “rough cuts” among the evaluated materials.

·

Conference participation. I expect active participation every day, so please be fully prepared

for each conference, preparation consisting of both reading and thinking

about the materials. Appended to this syllabus are some suggestions on

conference dynamics. If conference does not seem to be going well in your

opinion, please talk to me, and we will endeavor to remedy the situation. I

seek your comments and take them very seriously. Because we are a small group,

full and thoughtful participation throughout will greatly affect our conference

dynamics.

·

Four exploratories. Most of you have had courses with me before and so know what

I mean by “exploratory,” but I attach a reminder to the back of this syllabus

anyway and urge you to re-read it. Because this is an upper

level course, I will allow you as a group to decide whether they will be

due a day in advance (so I can read through them and orchestrate our

discussion) or due in conference itself. If the latter, there is a price to pay

as you will be called on in conference to introduce your topic and lead us in

brief discussion on it. (When introducing your chosen topic, feel free to call

on people to read out passages, express opinions, etc.) Note that a couple of

these exploratories will be narrower in focus than

normal and are intent on getting you to apply the readings to our image

database. (I want you to get as familiar as possible with our database to

improve your video productions.)

|

A Niutou demon at Fengdu |

·

One guided tour as Niutou 牛頭.

Niutou or “Ox head” is one of the guards and guides

of the underworld, often depicted with a pitchfork or mace in hand and

leading the damned to their tortures. Near the end

of the semester when we reach the 1970s, I will ask each of you in turn to

serve as our Niutou to get our conference started.

As Niutou, you will become the guide for fifteen to

twenty minutes, leading us through either Hsuan

Hua’s sermons or the Taiwanese monks’ personal explorations of hell. You can

highlight what you think is important and point out significant principles at

work. A good Niutou will do three things: 1.

In brief

compass summarize the argument (five minutes); 2.

Contextualize

that argument in terms of our syllabus (five minutes); 3.

And give

your own argument (five+ minutes). As

your followers (a.k.a. torture victims), we will reverently ask you questions

after your tour. |

·

And finally Purgatory Pictures presents...

·

The storyboard. Your first

teaching video task will be to develop your theme on paper, preparing the

initial draft of your script that also exhibits a consciousness of the images,

the visual and audio manipulation techniques and so forth along with the

content. CIS will help us define the parameters for our storyboards. Note “our”

– I’m going to be learning and producing alongside

you! (Think of the storyboard as on par with the first formal paper.)

·

The rough cut. Here the

storyboard will be translated into the first attempt at a four- to five-minute

teaching video. Again CIS will help us define the

parameters, and we’ll spend some time as a group critiquing our work,

suggesting ways to then finally develop...

·

The final cut. This piece

will be your contribution to the Purgatory Pictures playlist.

·

The textual support. On the website,

each teaching video will also link to a supporting document that supplies all

the citations, bibliographic material, image links, external links and

suggested further readings. Furthermore, it will include an analytical essay on

the theme of your teaching video production that takes the reader well beyond

your script, contextualizing and analyzing your theme as fully as possible.

(Think of this essay as on par with a final paper. Please include a

self-addressed, stamped envelope if you want comments.)

III. Incompletes, absences and extensions –

the draconian stuff so PLEASE READ

As the great Warring States legalist Han Feizi warned, indulgent parents have rowdy kids and overly

lenient rulers have inefficient subjects; by extension, a permissive teacher

can’t maximize a student’s learning potential. By laying down the law now, we’ll also never need to raise it again in the future, and I

can pretend to be a kindly Confucian rather than a draconian legalist.

“An Incomplete [IN] is permitted in a course where the level of work done up to

the point of the [IN] is passing, but not all the work of a course has been

completed by the time of grade submission, for reasons of health or extreme

emergency, and for no other reason,” according to the Reed College Faculty Code

(V A). “The decision whether or not to grant an IN in a course is within the

purview of the faculty for that course.”

Like many of my colleagues, I read this as restricting incompletes to

acute, extreme emergencies and health crises that have a clear beginning date

and a relatively short duration only, that are outside the control of the

student, and that interrupt the work of a student who was previously making

good progress in a course. Incompletes cannot be granted to students unable to complete

coursework on time due to chronic medical conditions or other kinds of ongoing

situations in their academic or non-academic life. Accommodation requests need

to be timely and go through established channels.

Regular, prepared, and disciplined conferencing is intrinsic to this course,

and so at a certain point when too many conferences have been missed –

specifically more than six which translates into a “fail”

for the course – it would logically be advisable to drop or withdraw and to try

again another semester. There’s no shame in that.

Longer-term emergencies indeed happen, and you ought to make use of Student

Services when they do. In sum, I’ll help you out as

much as I can to get you across the finish line, but it’s the same finish line

for everyone and to be fair to your colleagues I need to have you there in the

race. To that end, I would ask that you

please email me whenever you are absent just to let me know you’re okay. (More and more students seem to be doing this

without prompting anyway, perhaps because we’ve all

become increasingly dependent upon virtual connectivity.)

I’m happy to give paper extensions for medical

problems and emergencies, and you should take advantage of the Health and

Counseling Center in such circumstances. Please note that here, too, the honor

principle provides a standard for expectations and behavior, meaning that none

of us (including myself) should resort to medical reasons when other things are

actually impeding our work. (Please just be honest. It’s as simple as that.) In non-medical situations, late

papers will still be considered, but the lateness will be taken

into account and no comments given. Ken’s Subjectivity Curve: The later it

is, the more subjective Ken becomes. It's a gamble. I’m not a legalist like Han Feizi,

but even the Confucians resorted to hard law when ritualized conduct and

exemplary leadership failed.

Karmic

retribution for missing a conference

IV. Syllabus

Introductory week

|

23 Jan |

Now hiring: A Chinese Virgil |

Introduction |

|

25 Jan |

First survey of our hellish terrain |

Familiarization with “Taizong’s hell:

A study collection of Chinese hell scrolls” at http://www.reed.edu/hellscrolls/ |

|

27 Jan |

Filming the fiery

landscape |

[with CIS] A day to learn the

theories behind creating a high-quality teaching video, overviewing the

process from storyboarding to final production. |

A psychological earthquake?

Medieval China imports hell and reincarnation in the 1st-6th

centuries

|

30 Jan |

First principles from our

perspective |

·

Teiser, The scripture of

the ten kings, 1-15 (Text). ·

Faure,

Unmasking Buddhism, 44-48 (Moodle). ·

Eberhard,

Guilt and sin in traditional China, 12-59 (Moodle). |

|

1 Feb |

First principles from their

perspective |

·

Gardiner

1-14, 19-28, 33-36 (Text). ·

The questions of King Milinda

(Handout). ·

The Bodhidharma anthology (Handout). ·

Go

to Kieschnick’s http://religiousstudies.stanford.edu/a-primer-in-chinese-buddhist-writings/, click “English translation

key for volume 2” and read pp. 15-21. |

|

3 Feb |

Hell in the Buddhist nikāya

Exploratories |

Dirghāgama ·

Go

to Kieschnick’s http://religiousstudies.stanford.edu/a-primer-in-chinese-buddhist-writings/, click “English translation

key for volume 2” and read pp. 1-14. Majjhima nikāya ·

Nānamoli, The middle length

discourses of the Buddha, o 168-173 (“Four kinds of

generation” and “The five destinations and Nibbāna”); o 1016-1028 (“Bālapandita sutta”); and o 1029-1036 (“Devadūta sutta”) (all on Moodle). Samyutta nikāya ·

Bodhi,

The connected discourses of the Buddha, o 700-705 (“Lakkhanasamyutta”)

(Moodle). Anguttara nikāya ·

Bodhi,

The numerical discourses of the Buddha, o 205 (“Stains”); o 233-237 (“Messengers”); o 331-335 (“A lump of salt”); o 465-468 (“Unshakable [through

“Darkness”]); o 1090-1094 (“Fire”); o 1452-1455 (“Kokālika”): and o 1544-1547 (“Similarity”) (all

on Moodle). |

|

6 Feb |

Hell in Lingbao Daoism |

·

Miller,

Doing time in Taoist hell, 1-57

(“Introduction” and “Scripture on the great precepts in the upper chapter of

the Numinous Treasure from the most high cavern of the

sublime on wisdom and the roots of sin”) (Moodle). ·

Miller,

Doing time in Taoist hell, 92-130

(“Scripture on the most high perfected being of the sublime unity explicating

the exhortations and precepts concerning the five sufferings of the three

lower paths [of existence]”) (Moodle). |

||

|

8 Feb |

Twenty-five visits to hell in early folklore |

Campany, Signs from the Unseen Realm (all on Moodle): |

||

|

·

5:

77-84 ·

6:84-86 ·

22:

112-114 ·

23:114-116 ·

26:

120-124 ·

30:

128-130 ·

35:

134-135 ·

44:

145-148 ·

45:

148-154 |

·

54:

160-162 ·

59:

167-168 ·

65:

174-180 ·

66:

180-183 ·

67:

183-184 ·

68:

184-185 ·

77:

194-196 ·

80:

197-199 |

·

92:

216-217 ·

102:

227-228 ·

104:

229-230 ·

115:

241-242 ·

116:

242-243 ·

118:

245-246 ·

119:

247-249 ·

125:

256-257 |

||

Hell in the 9th-13th

centuries

|

10 Feb |

Dunhuang and the earliest excavated hell scrolls I Exploratories |

·

Teiser, The scripture of

the ten kings, 19-84 (Text). |

|

13 Feb |

Dunhuang and the earliest excavated hell scrolls II |

·

Teiser, The scripture of

the ten kings, 87-121, 152-79 (Text). |

|

15 Feb |

Dunhuang and the earliest excavated hell scrolls III |

·

Teiser, The scripture of

the ten kings, 180-218 (Text). |

|

17 Feb |

Excavated hell narratives at Dunhuang Exploratories |

·

Teiser, The ghost festival

in medieval China, 48-54 (Moodle); ·

Gardiner,

Buddhist hell, 37-79 (Text). |

|

20 Feb |

Paintings and sculptures of hell in the 13th

century |

·

Ledderose, “The bureaucracy of hell,” in Ten thousand things, 163-85 (Moodle); ·

Howard,

Summit of treasures: Buddhist cave art

of Dazu, China, 1-10, 38-55 (Text

provided by Ken). |

|

22 Feb |

Project Day I |

[with CIS] A day to learn

pre-production techniques and storyboard development |

Hell in the 16th-18th

centuries

|

24 Feb |

Taizong goes to hell |

·

Yu

(trans.), The journey to the West,

214-55 (Moodle). ·

Lin

and Schulz (trans.), The tower of

myriad mirrors, 65-87 (Moodle). |

|

27 Feb |

Yue Fei goes to hell |

·

Yang

(trans.), General Yue Fei, 852-869

(Moodle). ·

Gardiner,

Buddhist hell, 113-156 (Text). |

Hell in the 19th

century

|

1 Mar |

Jade records I |

·

Gardiner,

Buddhist hell, 81-103 (Text). ·

Donnelly,

A journey through Chinese hell,

107-27 (Text provided by Ken). |

||||

|

3 Mar |

Jade records II |

·

Clarke,

The Yü-li or Precious records. Please read o the whole of the first hell

(pp. 233-269); o the whole of the tenth hell

(pp. 389-400); o the introductions to the rest

(e.g. the “exhortation,” the “address,” the “new

decree,” the “proviso” – i.e. anything that’s not a numbered anecdote); and o the following twenty-five

numbered anecdotes: |

||||

|

21 23 24 26 28 |

29 33 37 43 44 |

57 69 71 75 87 |

93 94 99 106 108 |

109 114 141 143 145 |

||

|

6 Mar |

Purgatory pictures I |

Storyboards due |

||||

|

8 Mar |

Project Day II |

[with CIS] A day to learn how to

gather media and using them in the project. |

||||

Secondary studies on Chinese

hell

|

10 Mar |

Counting and transferring merit |

·

Kohn,

“Counting good deeds and days of life,” 833-64 (Moodle); ·

Brokaw,

“Spiritual retribution and human destiny,” 425-36 (Moodle); ·

Mollier, “Karma and the bonds of kinship,” 171-181 (Moodle). |

|

20 Mar |

Bureaucracy, punishment and

Confucian mercantilism |

·

Cline

and Littlejohn, “The bureaucracy of hell: Moral prioritization and

quantification in Chinese tradition,” 9-28 (Handout). ·

Brook,

Bourgan and Blue, “Tormenting the dead,” in Death by a thousand cuts, 122-51 (Moodle). ·

Guo

Qitao, Ritual

opera and mercantile lineage, 103-132 (Moodle). |

|

22 Mar |

Locally defined or universal phenomenon? |

·

Mākandeya

purāna (Handout). ·

St. Patrick’s purgatory (Handout). ·

Baxter’s

A divine revelation of hell (Handout). |

|

24 Mar |

Project Day III |

[with CIS] A day to learn how to

edit. |

Saviors descend into hell in 18th-19th

century literature

|

27 Mar |

Guanyin |

·

Yű, “Miao-shan/Kuan-yin

as savior of beings in hell,” in Kuan-yin, 320-33

(Handout); ·

Idema,

“The precious scroll of Incense mountain, Part II,”

99-159 (Text provided by Ken). |

|

29 Mar |

Mulian I |

·

Grant

and Idema, “The precious scroll of the three lives

of Mulian,” in Escape

from blood pond, 3-31, 35-76 (Text). |

|

31 Mar |

Mulian II Exploratories |

·

Grant

and Idema, “The precious scroll of the three lives

of Mulian,” in Escape

from blood pond, 76-145 (Text). |

|

3 Apr |

Woman Huang |

·

Grant

and Idema, “Woman Huang recites the Diamond sutra,” in Escape from blood pond, 31-34, 147-229

(Text). |

Other 18th-20th

century collections of hell scrolls

|

5 Apr |

The Donnelly collection |

·

Donnelly,

A journey through Chinese hell,

8-105 (Text provided by Ken). |

|

7 Apr |

Purgatory pictures II |

Rough cuts due |

|

10 Apr |

Workshop day |

A day to piece

together our teaching videos |

Hell in the 20th

century

|

12 Apr |

Dizang in 1970s’ preaching I Niutou: ____ |

· Zhiru, The making of a savior bodhisattva, 107-17. · Hsűan Hua, Sūtra of the past vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva, 17-89 (Text provided by Ken). |

|

14 Apr |

Dizang in 1970s’ preaching II Niutou: ____ |

· Hsűan Hua, Sūtra of the past vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva, 90-166 (Text provided by Ken). |

|

17 Apr |

Dizang in 1970s’ preaching III Niutou: ____ |

· Hsűan Hua, Sūtra of the past vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva, 167-227 (Text provided by Ken). |

|

19 Apr |

Touring hell in the 1970s I Niutou: ____ |

· Pas, “Journey to hell: A new report of shamanistic travel to the courts of hell,” Journal of Chinese religions 18 (1990): 43-60 (ATLA); · Orzech, “Mechanisms of violent retribution in Chinese hell narratives,” Contagion 1 (1994): 111-26 (http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/contagion/summary/v001/1.orzech.html); · Shahar, Crazy Ji: Chinese religion and popular literature, 189-95. · Voyages to hell, through Chap. 4 (pp. 1-41) (http://www.voyagestohell.com/). |

|

21 Apr |

Touring hell in the 1970s II Niutou: ____ |

· Courts 1-3, Voyages to hell, chaps. 5-21 (pp. 42-158) (http://www.voyagestohell.com/). |

|

24 Apr |

Touring hell in the 1970s III Niutou: ____ |

· Courts 4-6, Voyages to hell, chaps. 22-41 (pp. 159-290) (http://www.voyagestohell.com/). |

|

26 Apr |

Touring hell in the 1970s IV Niutou: ____ |

· Courts 7-10, Voyages to hell, chaps. 42-61 (pp. 290-429) (http://www.voyagestohell.com/). |

|

28 Apr |

Purgatory pictures

III |

Final cuts due Your first screening of their final screaming. |

|

10 May |

|

Textual supports due (with

SASE if you want comments) |

Fresh from “Make-up,” Yama is ready

for his close up.

V. Consciousness of conference technique

Much

of our educational system seems designed to discourage any attempt at finding

things out for oneself, but makes learning things others have found out, or

think they have, the major goal. –

Anne Roe, 1953.

At times it is useful to step back and

discuss conference dynamics, to lay bare the bones of conference communication.

Why? Because some Reed conferences succeed; others do not. After each

conference, I ask myself how it went and why it progressed in that fashion. If

just one conference goes badly or only so-so, a small storm cloud forms over my

head for the rest of the day. Many students with whom I have discussed

conference strategies tell me that most Reed conferences don't

achieve that sensation of educational nirvana, that usually students do not

leave the room punching the air in intellectual excitement. I agree. A

conference is a much riskier educational tool than a lecture, and this tool

requires a sharpness of materials, of the conferees and of the conference

leader. It can fail if there is a dullness in any of the three. Yet whereas

lectures merely impart information (with a "sage on the stage"),

conferences train us how to think about and interact with that information

(with a "guide on the side"). So when it does work....

The

content of what you say in conference obviously counts most of all, so how do

you determine in advance whether you’ve got something

worthwhile to say? The answer is simple if you don’t

just quickly read the assigned materials and leave it unanalyzed. So how do you

analyze it? A colleague and friend at Harvard, Michael Puett,

writes, “the

goal of the analyst should be to reconstruct the debate within which such

claims were made and to explicate why the claims were made and what their

implications were at the time." A

religious or philosophical idea doesn’t get written

down if everyone already buys it; it’s written down because it’s news. As new,

we can speculate on what was old, on what stimulated this reaction. Think of these texts as arguments and not

descriptions, and as arguments, your job is to play the detective, looking

for contextual clues and speculating on implications. I will give you plenty of

historical background, and if you look at these texts as arguments, you will

get a truer picture.

In

addition to content, there are certain conference dynamics that can serve as a

catalyst to fully developed content. I look for the following five features

when evaluating a conference:

1.

Divide the allotted time by the

number of conference participants. That resulting time should equal the

leader's ideal speaking limits. (I talk too much in conference. Yet when I say

this to some students, they sometimes tell me that instructors should feel free

to talk more because the students are here to acquire that expertise in the

field. So the amount one speaks is a judgment call,

but regardless, verbal monopolies never work.)

2.

Watch the non-verbal dynamism. Are

the students leaning forward, engaging in eye contact

and gesturing to drive home a point such that understanding is in fact taking on a physical dimension? Or are

they silently sitting back in their chairs staring at anything other than

another human being? As a conference leader or participant, it's

a physical message you should always keep in mind. Leaning forward and engaging

eye contact is not mere appearance; it indeed helps to keep one focused if

tired.

3.

Determine whether the discourse is

being directed through one person (usually the conference leader) or is

non-point specific. If you diagram the flow of discussion and it looks like a

wagon wheel with the conference leader in the middle, the conference has, in my

opinion, failed. If you diagram the flow and it looks like a jumbled,

all-inclusive net, the conference is more likely to have succeeded.

4.

Determine whether a new idea has been

achieved. By the end of the conference, was an idea created that was new to

everyone, including the conference leader? Did several people contribute a Lego

to build a new thought that the conferees would not have been able to construct

on their own? This evaluation is trickier because sometimes a conference may

not have gone well on first glance but a new idea evolved

nonetheless. The leader must be sure to highlight that evolution at conference

end.

5.

Watch for simple politeness.

"Politeness" means giving each other an opportunity to speak,

rescuing a colleague hanging out on a limb, asking useful questions as well as

complimenting a new idea, a well-said phrase, a funny joke.

If you ever feel a conference only

went so-so, then instead of simply moving on to the next one, I would urge you, too, to evaluate the conference using your

own criteria and figuring out how you (and I) can make the next one a more

meaningful experience. Preparation is

not just reading the assigned pages; it’s reading and

then thinking through something in that reading, developing a thought and

getting it ready to communicate to someone else.

In

the end, as long as you are prepared and feel

passionate about your work, you should do well, and if passion ever fails, grim

determination counts for something.

VI. The exploratory

Sometimes conferences sing. Yet just

when I would like them to sing glorious opera, they might merely hum a bit of country-western. After my first year of teaching at Reed, I

reflected upon my conference performance and toyed with various ideas as to how

to induce more of the ecstatic arias and lively crescendos, and I came up with

something I call an "exploratory."

Simply

put, an exploratory is a one-page, single-spaced piece in which you highlight

one thought-provoking issue that caught your attention in the materials we are

considering. This brief analysis must show thorough reading and must show your own thoughtful extension –

·

Your own informed, constructive criticism of the author

(and not just a bash-and-trash rant);

·

Your own developed, thoughtful

question (perhaps even inspired by readings from other classes) that raises

interesting issues when seen in the light of the author's text;

·

Your own application of theory and

method to the primary source;

·

Your own personal conjecture as to

how this data can be made useful; or (best of all)

·

Your own autonomous problem that you

devised using the same data under discussion.

I am not here looking for polished

prose or copious (or any) footnotes – save all that for our formal papers. (I

do not return exploratories with comments unless a

special request is made.) Exploratories are not full, open-heart surgeries performed

on the text. Instead, exploratories tend to be

somewhat informal but focused probes on one particular aspect

in which you yourself can interact with the text and can enter into the

conversation.

What

is not an exploratory? It is not

merely a topic supported by evidence from the book, nor is it a descriptive

piece on someone else's ideas, nor is it a general book report in which you can

wander to and fro without direction. Bringing in

outside materials is allowed, but the exploratory is not a forum for ideas

outside that day's expressed focus. (Such pieces cannot be used in our

conference discussions.) Also, don’t give into the temptation of just reading the first few

pages of a text and then writing your exploratory. (What would you conclude if you received a lot of exploratories that all coincidentally tackled an issue in

the first five or six pages of the reading?)

It is instead a problematique, an issue with

attitude.

The

best advice that I can give here is simply to encourage you to consider why I am requesting these exploratories from you: I want to see what ignites your

interest in the text so I can set the

conference agenda. That is why they are due the evening before a conference. Thus

late exploratories are of no use. (Being handed a

late exploratory is like being handed your salad after you've

eaten dessert and are already leaving the restaurant.) I base roughly a third to half my conferences

on exploratories, and I will use them to draw you in,

parry your perspective against that of another, and build up the discussion

based on your views. Exploratories help me turn the

conference to issues that directly interest you. They often lead us off on

important tangents, and they often return us to the core of the problem under

discussion. So if you are struggling with finding

"something to say," simply recall why I ask for these exploratories in the first place. Is there something in the

text you think worthy of conference time? Do you have an idea you want to take

this opportunity to explore? Here is your chance to draw our attention to it.

Your perspectives are important, and if you have them crystallized on paper in

advance, they will be easier to articulate in conference.

Since

I began using exploratories, most students have

responded very favorably. Students like the fact that it is a different form of

writing, a bit more informal and more frequent, somewhat akin to thinking

aloud. It forces one not just to read a text but to be looking for something in

that text, to engage that text actively. And it increases the likelihood that

everyone will leave the conference singing Puccini.